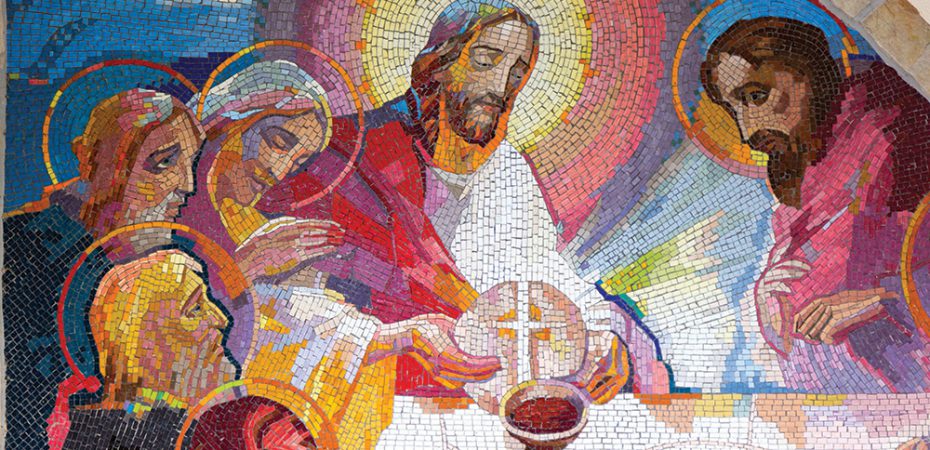

The Eucharist

How belief in the Real Presence has shaped Catholicism for 2,000 years

Father Douglas J. Milewski Comments Off on The Eucharist

Last summer’s Pew Research report that 69% of American Catholics believe Jesus Christ is only symbolically present in the Eucharist drew both understandable attention and merited criticism of its methodology and conclusions. It also occasioned an opportunity to consider how belief in the Real Presence has shaped Catholicism for 2,000 years.

A priest’s comment from the Great Jubilee came to mind, who likened distributing holy Communion at a papal liturgy to helping Peter fulfill the Lord’s mandate, “Feed my sheep” (cf. Jn 21:15-17). The Eucharist entered the Church’s life by way of the commandment — “Take and eat” (Mt 26:26), “Drink” (Mt 26:27), “Do this in remembrance of me” (1 Cor 11:24-25) — so that “the breaking of the bread” (Acts 2:42, 46) characterized the original Jerusalem community, passing down the centuries from the chief apostle to the whole apostolic Church.

Accordingly, Peter’s successors frame these reflections: from Christianity’s beginnings with St. Ignatius of Antioch, to the Council of Trent’s Eucharistic doctrine, to the “Eucharistic agenda” of Pope St. John Paul II.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

St. Teresa of Calcutta’s Message about the Eucharist

We cannot separate our lives from the Eucharist; the moment we do, something breaks. … Our lives must be woven around the Eucharist. Ask Jesus to be with you, to work with you that you may be able to pray the work. You must really be sure that you have received Jesus. After that, you cannot give your tongue, your thoughts or your heart to bitterness.

Put your sins in the chalice for the precious blood to wash away. One drop is capable of washing away all the sins of the world. …

We must be faithful to that smallness of the Eucharist, that simple piece of bread which even a child can take in. … We have so much that we don’t care about the small things. If we do not care, we will lose our grip on the Eucharist — on our lives. The Eucharist is so small.

I was giving Communion this morning. My two fingers were holding Jesus. Try to realize that Jesus allows himself to be broken. Make yourselves feel the need of each other. The Passion and the Eucharist should open our eyes to that smallness: “This is my Body; take and eat” — the small piece of bread. Today let us realize our own littleness in comparison with the Bread of Life.

— Quotes of St. Teresa of Calcutta from Brother Angelo Devananda’s “Mother Teresa: Contemplative in the Heart of the World,” Servant Books, $25.75)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

First Eucharistic ‘Mystic’

Antioch and Rome are Petrine sees, which the liturgical calendar once reflected with feasts for the Chair of Peter at Rome (Jan. 18) and Antioch (Feb. 22). Ignatius’ letters to the churches at Rome, Ephesus, Philadelphia, Smyrna, Tralles and Magnesia, composed en route to his martyrdom in circa A.D. 110, are of the highest importance for understanding nascent Christianity and constitute a revered pastor’s final bequest. Years of community life, prayer and liturgy rendered Ignatius’ ideas on the Eucharist extremely consistent.

The central reality in his mind is the truth of the Incarnation. The marvelous shock that God really experienced human limitations and sufferings underscores everything Christians believe and do. He reiterates that Jesus Christ really did take flesh, suffer, die and rise in the flesh (cf. Ign Eph, Nos. 7, 16, 19; Ign Mag, No. 11; Trallians, Nos. 2, 9; Ign Phil, Nos. 3, 4, 8; Smyrnaeans, Nos. 1-3, 6-7, 12). Ignatius rejected a spiritualized redemption as deadly to humans who are anything but pure spirit. Rather, God’s love is shown by saving humans as humans, by becoming one with them himself.

The Christian Church’s task, therefore, is primarily to keep the presence of the Incarnation before the world so that Christ may continue to draw all peoples to himself. The one, incarnate Christ is present in the Sacrament through the liturgy of the one Church, which is itself renewed in unity. Unity is the basis and fruit of the Eucharist. Removed from the Incarnation, the Eucharist loses meaning; without the Eucharist as Real Presence, the Incarnation “shuts down,” becomes enclosed in time and lacks eschatological fulfillment.

Ignatius’ powerful, objective sense of the Eucharist as Christ’s Real Presence is paired with an equally dynamic sense of this. First, the importance of the liturgy as the vehicle for “making” the Eucharist is where he seems to see the Church as most authentically itself — Christ’s body in the world (cf. Ign Eph, Nos. 4, 5, 13, 20; Ign Mag, No. 7, 9; Trallians, No. 6; Ign Phil, No. 4, 9; Smyrnaeans 6). Encountering Jesus in the liturgy enables Christians to work for the salvation of the world, even of their enemies. It is a lack of charity, a kind of cruelty to absent oneself deliberately from the Eucharistic liturgy (Smyrnaeans 6).

Christ’s dynamic Real Presence also shapes each Christian’s life. One truly “becomes” a Eucharist; until then, one is learning discipleship. Ignatius speaks bluntly about becoming God’s pure bread ground by the beasts that will kill him (cf. Ign Rom, No. 4). This is not some zealot’s defiance, but the voice of a lifetime contemplating the Eucharist. “These are the beginning and end of life: faith is the beginning, and love is the end, and the two, when they exist in unity, are God” (Ign Eph, No. 14). “Faith” can be another way of referring to the Lord’s Eucharistic flesh and “love” to his blood (Trallians, No. 7, Ign Phil, No. 4). Christ’s birth and death and Mary’s virginity are three mysteries accomplished in God’s silence to achieve human salvation, a silence that Ignatius urges Christians to practice by living sincerely within the unity of the Church culminating in “breaking one bread, which is the medicine of immortality, the antidote we take in order not to die but to live forever in Jesus Christ” (Ign Eph, No. 15-20).

The fullness of Ignatius’ Eucharistic theology is remarkable — and at so early a date! He affirms the reality of Christ in the Sacrament, its intrinsic correlation to the Incarnation and Paschal Mystery, its basis for community life, its pattern for the individual Christian’s life, its transformative power, and its “naturalness” as an object of contemplation. He anticipates much that is in later patristic thought: the connection to martyrdom; the explicit linking of the Incarnation with the words of consecration; Eucharistic belief shaping Christology; ecclesiology grounded in the sacrifice of the altar; the living allegory of Scripture and liturgy. Yet nowhere does Ignatius claim this as his own teaching. Rather, he affirms what he believes is already established, sharing this as a fellow disciple who is still learning.

Trent: Doctrine and Devotion

The council convoked by Popes Paul III, Julius III and Pius IV provided the Church with comprehensive teaching on the Sacrament, showing the long fruition of the understanding evident in Ignatius. This eminently theological and pastoral achievement in eight chapters at Trent’s 13th session may be summarized as follow:

• Chapter 1: Christ’s Person is entirely, really and substantially contained in the Eucharist without contradicting his eternal presence at the Father’s right hand.

• Chapter 2: We thereby cherish his memory, nourish and strengthen our souls as an antidote to daily faults and protection against mortal sin, and have a sign of our unity in his body and the pledge of future eternal union with him.

• Chapter 3: The Eucharist is unique among the sacraments in that Christ is fully, truly met in a way based on the hypostatic union of the Incarnation even before the Sacrament is received in either form.

• Chapter 4: Transubstantiation is the Church’s most suitable and proper way to name the change the bread and wine undergo.

• Chapter 5: It is only right and reasonable that the Eucharist receive the most fitting worship of adoration.

• Chapter 6: It also becomes clear that reserving the Sacrament for the sick is an exercise of the Lord’s love for his people.

• Chapter 7: It is equally obvious why importance is placed on receiving the Sacrament as worthily as possible.

• Chapter 8: Hence, Christians are encouraged to receive the Eucharist sacramentally and spiritually — that is, to their souls’ full benefit.

Once one believes the Lord is fully, truly present “before” the reception of the Sacrament (chapter 3), his abiding Presence “after” the liturgical celebration (chapter 6) simply makes sense, a belief witnessed by the Church’s liturgies of Presanctified Gifts. Adoration of the Sacrament (chapter 5) logically follows this understanding, as does receiving the Eucharist as efficaciously as possible (chapters 7-8). The discussion of the nature of Christ’s Presence (chapter 1) and his manner of effecting it (chapter 4) attempt to bring this mystery as close within reason’s grasp as can be; for, the Divine Logos is the one present, just as he made himself flesh.

Preeminently, the Logos is Love. Christ’s Presence before, after and independent of receiving him is not some metaphysical puzzle but an act of love that anticipates and abides among its beloved. This Real Presence bestows gifts and graces drawing the beloved into himself (chapter 2). The teachings in chapters 5-8 are not mere juridical norms; they are eminently natural responses to supreme love. At the heart of Trent’s Eucharistic teaching is a dynamic of divine Love’s Real Presence and human love’s desire to respond.

The council’s terminology for the change of the bread and wine into the Lord’s body and blood reflects this dialogue of love, choosing conversio (conversion), rather than the more common word for “change,” mutatio or transformatio. Conversion, as willingly turning oneself over to God, is clearly not meant, but a more “technical” sense whereby something remains at the end of the change that was there originally (cf. the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia, “Eucharist”). This conversion is not a simple replacement, much less the annihilation or total loss, of the original thing. The endurance of the elements’ accidents in the Eucharistic miracle indicates this. Nevertheless, a most extraordinary change happens. The implication seems clear: If such is possible with inanimate creation, how much greater a miracle does God intend for the creature in his image and likeness? Hence, we do “put on Christ,” so that it is no longer we who live but Christ who lives in us (cf. Rom 13:14; Gal 2:20; 3:27).

Trent meant to settle matters by clarifying the Church’s belief about the Sacrament, and in so doing it unsettled matters by necessarily including the communicant’s profound change and conversion. It inspired a rich period of Eucharistic spirituality, devotion and liturgical celebration that still nourish Catholics.

John Paul II: Gratitude and Awe

In 1946, the year of his ordination, Father Karol Wojtyła marveled at the Eucharist in two poems. He adores the “pale light of wheat bread” for “in you eternity dwells but for a while, / flowing in to our shore / along a secret path.” He exults that “a morsel of bread is more real / than the universe, / more full of existence, more full of the Word.” The young priest’s awe never abandoned the aged pope, who promoted a Eucharistic vision for the third millennium. It is impossible to trace here that ample magisterium, but his mature thought emerges from the 2003 encyclical Ecclesia de Eucharistia, the 2004 apostolic letter Mane Nobiscum Domine and the 2005 Holy Thursday Letter to Priests.

The Church originates in the Upper Room equally at the institution of the Eucharist as at Pentecost. Each Mass returns to history’s decisive hour, Christ’s hour from which he would not retreat, the hour of our redemption. The Lord commissioned his Church to make this “hour” present through all time, creating a mysterious oneness between the Triduum and the passage of centuries (cf. Ecclesia de Eucharistia, Nos. 4-5). The resulting profound amazement and gratitude characterize the whole worshipping Church, but especially the minister (Nos. 5-6). Theological reflection becomes an exercise in love, exemplified by the Sacrament’s poet-theologian, St. Thomas Aquinas (No. 15). The Eucharist’s sacrificial nature makes full Communion with Christ occur; the sacrifice makes the Sacrament a true banquet. “This is no metaphorical food: ‘My flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed’ (Jn 6:55)” (No. 16).

Mane Nobiscum Domine announced the Year of the Eucharist, a “postlude” to the Great Jubilee. Trent taught the whole Person of Christ is met in the Sacrament; John Paul envisions a complete human response to his Presence. The totality of the encounter matches its intimacy.

“When the disciples on the way to Emmaus asked Jesus to stay ‘with’ them, he responded by giving them a much greater gift: through the Sacrament of the Eucharist he found a way to stay ‘in’ them” (Mane Nobiscum Domine, No. 19). This communion is only understood within an ecclesial mission and “plan” embracing society and culture (cf. No. 25). The Second Vatican Council’s description of the Eucharistic sacrifice as the “source and summit of the whole Christian life” (Lumen Gentium, No. 11) immediately comes to mind. The pope, thus, closes by exhorting bishops, priests, deacons, liturgical ministers, seminarians, consecrated men and women and all Christians to this mission and plan (Mane Nobiscum Domine, No. 30).

St. John Paul’s reflections culminated in his 2005 Holy Thursday Letter to Priests, written scant weeks before his death. He proposed a priestly spirituality based on the central mystery of their lives: the words of consecration. “For us, the words of institution must be more than a formula of consecration: they must be a ‘formula of life’” (Letter to Priests for Holy Thursday 2005, No 1):

• A life of profound gratitude, so that each priest’s life becomes an individual Magnificat.

• A life that is given, grounded in the Trinitarian life of God who is Love.

• A life that is saved in order to save, the whole individual and all individuals, integrally and universally.

• A life that remembers, especially the entire mystery of Christ in the Old and New Testaments.

• A consecrated life, that guards and manifests the sacredness of the Eucharist.

• A life centered on Christ, so others may see Christ and be won by Christ.

• A Eucharistic life at the school of Mary, who knows best the meaning of communion with her Son.

The pope desires each priest discover “his ever-renewed amazement at the extraordinary miracle worked at his hands” (No. 6). John Paul and Ignatius stand in comparison: two priests in their final days turning to the Eucharist to seal their last teachings and, indeed, their lives.

Fraternity

Professing the Real Presence affords no complacency to Christians who acknowledge the one Christ is truly present in the Eucharist of churches no longer in full communion with each other, including those sharing apostolic origin from St. Peter. A common Eucharistic belief and the absence of full communion chastens and fosters an urgency for ecumenical fraternity. It suggests another way Trent’s connection of conversion with the Eucharist finds application and for seeing theological reflection as an exercise in love, per Sts. Ignatius and John Paul.

One concrete exercise might be to build on John Paul’s “formula of life” from the words of consecration and amplify it to the Church’s ancient liturgies in their entirety. Vatican II encouraged such reflection over 50 years ago (cf. Unitatis Redintegratio, Nos. 15-17). The Eastern and Western liturgies represent richly human responses to the divine mystery they serve. Their language, theological elements, biblical allusions and structure all evoke exquisitely that dialogue of love the Eucharist embodies.

The Eucharist begins with a commandment from the Lord; any understanding of it must acknowledge it as the Church’s life source, her real food. From the dawn of Christianity through the greatest doctrinal upheaval to the threshold of the third millennium, the successors of the apostle first entrusted with that mandate have deepened the awareness of what is implied behind proclaiming, “This is my body. This is my blood.” No metaphor could provide so much.

FATHER DOUGLAS J. MILEWSKI, STD, is an associate professor of theology at Seton Hall University.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Eucharistic ‘Amazement’

“Mysterium fidei! — the Mystery of Faith! When the priest recites or chants these words, all present acclaim: “We announce your death, O Lord, and we proclaim your resurrection, until you come in glory.”

In these or similar words the Church, while pointing to Christ in the mystery of his passion, also reveals her own mystery: Ecclesia de Eucharistia. By the gift of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost the Church was born and set upon the pathways of the world, yet a decisive moment in her taking shape was certainly the institution of the Eucharist in the Upper Room. Her foundation and wellspring is the whole Triduum paschale, but this is as it were gathered up, foreshadowed and “concentrated” forever in the gift of the Eucharist. In this gift Jesus Christ entrusted to his Church the perennial making present of the paschal mystery. With it he brought about a mysterious “oneness in time” between that Triduum and the passage of the centuries.

The thought of this leads us to profound amazement and gratitude. In the paschal event and the Eucharist which makes it present throughout the centuries, there is truly an enormous “capacity,” which embraces all of history as the recipient of the redemption. This amazement should always fill the Church assembled for the celebration of the Eucharist. But in a special way it should fill the minister of the Eucharist. For it is he who, by the authority given him in the sacrament of priestly ordination, effects the consecration. It is he who says with the power coming to him from Christ in the Upper Room: “This is my body which will be given up for you. This is the cup of my blood, poured out for you …”. The priest says these words, or rather he puts his voice at the disposal of the One who spoke these words in the Upper Room and who desires that they should be repeated in every generation by all those who in the Church ministerially share in his priesthood.

I would like to rekindle this Eucharistic ‘amazement’ by the present Encyclical Letter.

— St. John Paul II, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, Nos. 5-6

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….