Lessons from St. Paul

Why the apostle’s experiences and qualities are especially pertinent to priests today

Father Donald Senior Comments Off on Lessons from St. Paul

Both personally and in the wider social and religious world of his day, Paul the Apostle witnessed an old world die and a new one born — not unlike our experience at this moment in history. Paul, of course, was not a priest but an apostle and dedicated lay missionary. But some of the characteristic experiences and qualities of Paul’s ministry, I believe, have special significance for today’s priesthood.

Perhaps more than any other figure in the early Church, Paul embodied profound conversion and transformation for the sake of the Gospel — both on a personal level and within the religious tradition to which he was passionately committed. Sometime around A.D. 5, Paul was born in Tarsus, a provincial capital in south-central Asia Minor, present-day Turkey.

Tarsus was a city noted for its culture and learning, a thoroughly Greco-Roman city, yet one with a significant Jewish minority population. We know that Paul was born into a devout Jewish family — a heritage he would always cherish and respect. Yet, he was also born of a father who was a citizen of Rome — we do not know how Paul a Jew acquired his Roman citizenship, perhaps because his father had been part of the military or was a freed slave. From this dual heritage — devotedly Jewish and proudly Roman — Paul would embody within himself the cultural and religious mix that would be key for his future mission.

From his Jewish heritage came a tenacious faith in the God of Israel, the compassionate, liberating God who had created the world and held it in his loving providence. And from Judaism, as well, Paul was endowed with a strong moral sense of translating one’s belief in God into a life obedient to God’s will. From his Roman heritage and his classical education in Tarsus, Paul would draw on a broad vision of the Mediterranean world in all its diversity and dynamism and be schooled in the art of rhetoric and persuasion that Rome had inherited from its Greek predecessors. Paul’s family tree, his DNA if you like, would be translated by God’s dynamic Spirit into a figure who would bridge the Mediterranean world.

Paul and Conversion

The New Testament gives us two portrayals of a crucial turning point in Paul’s life where his vocation from God would burst into flame. One is found in the dramatic conversion stories of the Acts of the Apostles. Paul, whose cocksure zeal drove him to persecute the followers of Jesus, would be knocked to the ground by the power of Christ’s redeeming presence. Blinded by the light of God’s forgiving love, Paul, paradoxically, would begin to see the truth for the first time (cf. Acts 9:3-19; 22:6-16; 26:12-18).

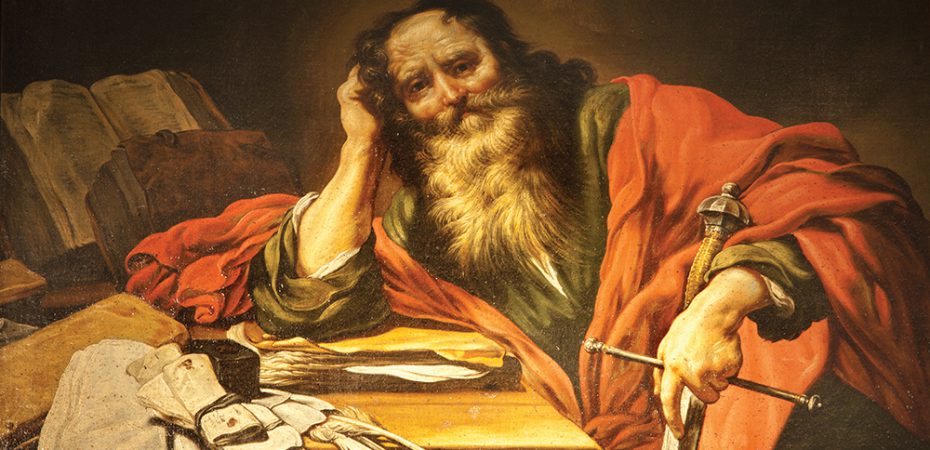

Renáta Sedmáková/AdobeStock

In Luke’s account of the unfolding history of the early community, Paul, the tormentor and persecutor of the Christians, would now become the “chosen vessel ” — the one who would bring the Gospel of Jesus from Judea to Antioch, westward to Greece and, ultimately, to Rome.

Thus, in the portrayal of the Acts of the Apostles, Paul’s conversion is, in a certain sense, forced from the outside — an experience beyond his control turns his religious world upside down and transforms his life forever.

The striking account of Paul’s conversion in Acts takes a very different form in Paul’s own words in his Letter to the Galatians (cf. Gal 1:11-24). Looking back, Paul now sees that God had been calling him to this extraordinary transformation from all time — even before he was knit together in his mother’s womb. He cites the great prophetic words of Isaiah 49 and Jeremiah 1 — “The word of the Lord came to me: / Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, / before you were born I dedicated you, / a prophet to the nations I appointed you.” (Jer 1:4-5).

The catalyst for radical change was not simply the turbulence of outside events but the fulfillment of a God-given destiny, an act of providence to which God had called Paul from all time.

Thus Paul steps into a beautiful and profound biblical tradition — that of the “call,” accounts of God’s mysterious call that stretch from Moses to the prophets and on to Mary and the disciples of Jesus in the New Testament. The Spirit of God beckoning mysteriously, tenaciously — inviting one to set out on a new and often unexpected way of life for the sake of God. Paul is one of these. “It is too little,” God whispers to Isaiah, “for you to be my servant, / to raise up the tribes of Jacob, / and restore the survivors of Israel; / I will make you a light to the nations, / that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth” (Is 49:6).

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Building the Church for Christ

We might also recall that Paul was someone who made no small plans, even though in those days, too, we might say vocations were sparse and finances precarious. As he indicates in Romans 15, Paul intended to plant churches all around the northern rim of the Mediterranean world, eventually going even to Rome and on to Spain, thus winning over the gentiles for Christ, a glorious accomplishment of God’s grace that he hoped would, in turn, convince all of Israel itself to accept Christ.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Authentic Modalities

All of us, I think, can reflect on these different but authentic modalities of our life and our vocation. On one level, we are driven by factors outside of us: world events, the threat of a pandemic, the economy, the changing face of the Church, the movements of culture and history, the encouragement of friends and mentors. And we surely need wise and caring people to help us sort through such experiences and to make sense of them. Like Paul, we need people to help us shed our blindness and see our life and the people around us from the perspective of our Christian faith.

But on another, equally important, level we also believe that we are held in God’s hands, our lives both individually and collectively a response to God’s profound call to us, a call imbedded in God’s loving providence for all time. And here we know the importance of reflection on the deepest wellsprings of our faith; reflection on the Scriptures and the great characters and saints of our heritage who also responded to God’s call and drank deeply of the wellsprings of Christian spirituality to understand what God was doing in their lives, just as Paul drew on the stirring words of Isaiah and Jeremiah, and the example of their prophetic ministries to make sense out of the unanticipated turns in his life. Perhaps, this is some of the work that needs to take place during sabbaticals or programs of reflection for ministers of the Gospel of all times.

The Passion of Paul

Paul, as you know, was not an original or charter member of Jesus’ disciples. Paul never forgot his second-generation status — or his wrongheaded persecution of the Christian movement. He would forever remain in his own estimation as one “born out of due time.” But that did not take away from Paul’s passionate commitment to Christ or the Gospel.

Paul’s passion was undoubtedly a product in part of a naturally fiery temperament. No even-tempered phlegmatic would express in a public letter like Galatians the hope that those Christians who proposed circumcision for his gentile converts would have the knife slip in their own case — or begin a letter to a prominent Church with the address: “O Stupid Galatians!” Paul, I fear, may not have been easy to live with. Perhaps it is no accident that his ministry was primarily an itinerant one!

But it is equally clear that the sustaining fire of Paul’s passion came from the intensity of his commitment to Christ. At one point in his life, Paul affirmed to his community the startling confession: “Christ lives in me.” It was this that drove him in his ministry, and from this came his preaching and his theology.

It was the passion of Paul that led him to write letters whose imagery and force changed Christian consciousness forever. Letters written in rapid, often tortured prose; letters so bursting with ideas that more than one scribe at a time had to take Paul’s dictation; and even another inspired biblical author had to say, with some understatement, there are things in the writings of our brother Paul that are hard to understand (cf. 2 Pet 3:15-16).

My point is that Paul’s ideas — his preaching, his writing, his theology, his teaching, his sense of authority and governance — were welded to his own passionate discipleship. Paul’s theology was not borrowed or trendy or merely speculative. Paul derived his vision from the living soul of the Church and his own passionate commitment to it. He was the recipient and responsible guardian of tradition: “For I handed on to you as of first importance what I also received” (1 Cor 15:3). But he also was able to draw out a theological vision from the genuine Christian experience of his people: the Church as the Body of Christ in response to the factionalism of Corinth; a theology of weakness in the face of his, and his Christians’ own experience of limitation — physical and spiritual; a theology of a law-free Gospel because of his confidence in the religious experience of gentiles; a theology of a cosmic Christ triumphant over the cosmos to offset the paralyzing fear of fates so prevalent in the Greco-Roman world.

The heart of Paul’s theology and his spirituality was linked to another experience of passion — namely, the passion of Jesus. For Paul, the dying and rising of Jesus Christ was the reality that explained all reality, that revealed the true face of God. In the light of the Passion, of the Paschal Mystery, Paul rethought and rediscovered the heart of his Jewish tradition. The God of Abraham was also the God of the Nations. The God of Jesus crucified was revealed not in the trappings of power and splendor but in the marvel of what some humans counted as weakness: a life poured out for others.

“For Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are called, Jews and Greeks alike, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.” (1 Cor 1:22-25).

From this center, Paul would contemplate everything: the heart of Christian life was love, as it was unconditional love that animated the crucified Christ; the experience of limitation and weakness, as Paul himself experienced in his own mortal body, would find meaning in the crucified body of Jesus who gave himself for us; the Body of Christ that was the Church would give the greatest honor to its most weak and least honorable member because God had revealed himself to the world through a crucified Messiah, and thus the Body of Christ was a crucified body in which the wounds were still visible; and the apostolic sufferings and wrenching heartache Paul experienced in the course of his ministry, and which his communities experienced in their struggles and sufferings, were not in vain because the cross of Jesus had forever affirmed that through God’s grace from death comes abundant life.

Confident Leader

I think all of us who work in the Church today can learn something about authentic apostolic leadership from Paul, too, and about the image of the Church we need to project to those we serve. Paul was very conscious of his role as an “apostle of Jesus Christ” and cites it frequently. Yet, it would be a misunderstanding of Paul and his ministry to think of him (as has sometimes been the case) as some solitary colossus standing astride the early Church or as a lone ranger, moving fearlessly and alone across the map of the Mediterranean world, planting the seed of the Gospel without dependence on or connection with others.

This image is false, and our evidence is Paul’s own testimony. One of the most remarkable and important insights we have gained into Paul in recent times is that he operated within an extraordinary network of co-workers. Paul did not shrink from the demands of leadership or the responsibility of authority, but he exercised that calling in a manner compatible with his own theology of the passion and of the community that belonged to Christ.

The famous concluding passage in Romans 16 is one of the best sources of evidence for this. As Paul concludes this letter to a Church he has never visited, but one that had great importance to him, he adds a series of greetings that gives breathtaking insight into the range of his contacts and his non-possessive spirit, as well as testimony to the mobility and networking of the early Christians themselves. He cites by name 29 Greek and Jewish co-workers and fellow “apostles” (10 of them women), drawn from nobility, freedmen and slaves.

Paul never traveled alone; he hands out the title “co-worker” liberally throughout his letters, and even his letters themselves are collaborative pieces, all but two of them are explicitly co-authored. Paul’s sense of collaboration was not simply a personal style or imposed by necessity, but flowed from his vision of the Gospel, rooted ultimately in his image of the God who gathered all people, who was the God of Jews and gentiles. A conviction that spills over into Paul’s consistently collaborative images of the Church as a body of many members, as a profusion of gifts welded into one Spirit, as an array of many instruments and materials fashioned into one living temple of God.

The building up of the community of the Church was his restless apostolic goal, and he knew that every gift, no matter how brilliant, was subordinate to the gift of charity and the bonding of the community.

Paul’s own theology of weakness put the ultimate check on the temptation to possessiveness about one’s status or authority. Paul’s own evident physical disability, his wrongheaded persecution of the Church early in his life — all these experiences had taught Paul his own moral fragility and led him to find his strength, paradoxically, in his own weakness, because where he was weak, God was strong. Above all, Paul’s contemplation of the Passion protected him from conceiving of himself or his authority in arrogant terms. Jesus, God’s Suffering Servant, who gave his life that others might live, was the ultimate sign of how authentic authority was exercised.

That memory of Paul is needed now. Those who exercise authority in the Church — no matter at what level — need confidence in their apostolic vocations, but also need to hold them in a non-possessive way. Collaboration with others in our ministry and our vision of the Church is not a fad but an expression of the Gospel.

Boundless Man of Hope

Allow me to cite one final characteristic of Paul. I am convinced from reading Paul’s letters that he was a man who suffered greatly from his ministry, yet at the same time it was the consuming passion of his life. Paul’s ardent zeal for Christ and the Gospel ran headlong into unyielding reality. Paul’s heart was broken not just by the dreams that never took flesh but by the constant drumfire against the few things he had been able to build. Truth squads of other Christian leaders seemed to have stalked his steps, questioning his orthodoxy, turning the heads of his converts to a different understanding of the Church, planting doubts about his apostolic authority.

Paul’s anguish and frustration come to a rolling boil in a famous passage from 2 Corinthians 11, as if on some blue Monday, Paul’s patience breaks and out comes a torrent of frustration and pain, directed not at the leaders of the synagogue, or at the threats of Roman officials, but at his own fellow apostles and the leaders of his own communities:

”Are they Hebrews? So am I. Are they Israelites? So am I. Are they descendants of Abraham? So am I. Are they ministers of Christ? (I am talking like an insane person.) I am still more, with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, far worse beatings, and numerous brushes with death. Five times at the hands of the Jews I received forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods, once I was stoned, three times I was shipwrecked, I passed a night and a day on the deep; on frequent journeys, in dangers from rivers, dangers from robbers, dangers from my own race, dangers from Gentiles, dangers in the city, dangers in the wilderness, dangers at sea, dangers among false brothers; in toil and hardship, through many sleepless nights, through hunger and thirst, through frequent fastings, through cold and exposure. And apart from these things, there is the daily pressure upon me of my anxiety for all the churches. Who is weak, and I am not weak? Who is led to sin, and I am not indignant?” (vv. 22-29).

Paul lived at a time when his vision of the Church was contested by others. There must have been nights in Corinth or Thessaloniki or Ephesus — surely in Jerusalem or during house arrest in Caesarea and Rome — when he wondered if he was on the wrong track after all. Maybe thoughts like these have passed through the minds and hearts of priests as they exercise their ministry and take stock of its results.

Holding on Tightly to Hope

But, at the same time, Paul managed what every great pastoral leader has done. Paul held tightly to his hope. Paul never let go of his foundational experience of faith. The love of the crucified Christ for him was the pledge of God’s unbreakable covenant, of God’s unceasing redemptive love for the world: “What will separate us from the love of Christ?” (Rom 8:35), Paul asks.

It is a question wrung from the heart of a minister of the Gospel, of one called to mission, of an adult who has lived in the Church from the inside and who still refuses to be undone by its scandals and frustrations; one who had lofty ideals of community but also knew the sad realities of divisions and conflicts; one, in effect, who knew the reality of suffering and yet nourished great hopes.

He says in the most soaring passage of his letters, “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38-39).

As priests and ministers of the Gospel, called to live out our faith in the Christian mission at this moment in history, a mission that takes many forms and that has its moments of joy, no doubt, but also its share of discouragement and frustration and solitariness, we might do well to remember Paul: a passionate disciple of the crucified Jesus and theologian of experience; one whose God-given call to service was nourished by others; a man confident in his apostolic vocation and identity but exercising his authority in a collaborative and non-possessive way, holding that treasure with others not because it was an attractive management style but because it was expressive of Christian faith; a man open to new possibilities, one whose restless, bold dreams for the Church brought him suffering but whose hope, rooted in faith, never dimmed.

FATHER DONALD SENIOR, CP, is president emeritus and chancellor of Catholic Theological Union in Chicago (CTU), where he is also a member of the faculty as professor of New Testament.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Paul’s Life and Theology

From the very first moment of his encounter with the Risen Christ, Paul felt called by God to proclaim the Gospel not just to his fellow Jews but to the gentile world. There was no gap, no long pondering that led after time to this decision. From his own testimony, Paul was convinced of the Gospel’s life-giving force for all of humanity from the very first instant of his encounter with Christ.

Paul’s urgent missionary logic is clear in this famous passage from his letter to the Romans: “For ‘everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.’ But how can they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how can they believe in him of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone to preach? And how can people preach unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring [the] good news!’” (Rom 10:13-15).

Even though Paul testifies that he was called to be a missionary to the gentiles from the first moment he encountered the Risen Christ (cf. Gal 1:15-16), still, no doubt, it took time and the assistance of others for Paul to further develop his initial vocation. By his own testimony, he spent considerable time in prayer and solitude in Syria, near Damascus, and then went for a brief time to Jerusalem to confer with Peter and James (cf. Gal 1:17-20). Afterward, he went to Cilicia (his home region in southern Asia Minor) and eventually to the major city of Antioch, which would be his first true missionary base.

Paul was drafted by Barnabas and brought to Antioch to join him in the new adventure of proclaiming the Gospel to the Mediterranean world that lay beyond the perimeters of Israel. Here, Acts tells us, the followers of Jesus were first called “Christians” and here Paul, under the guidance of Barnabas and others, would hone his message for gentile Christians and, from here, he would launch his missionary journeys west through Asia Minor and eventually to Greece when he first set foot on what would be European soil and where he would establish a Christian community at Philippi (cf. Acts 16:11-12).

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………