In the footsteps of the Good Shepherd

How to listen and discern the voice of the Master

Father Michael Connors Comments Off on In the footsteps of the Good Shepherd

Even as a boy I marveled at the wide variety of devotions and images attached to Jesus Christ, our Savior. The spiritualities he has inspired in our Catholic tradition are such great wealth for us. Of course, the approaches to Jesus in the days before the Second Vatican Council seemed to be dominated by two: (1) Jesus in agony on the cross suffering for our sins, and (2) Jesus the mighty judge of all at the end of our lives and the end of time.

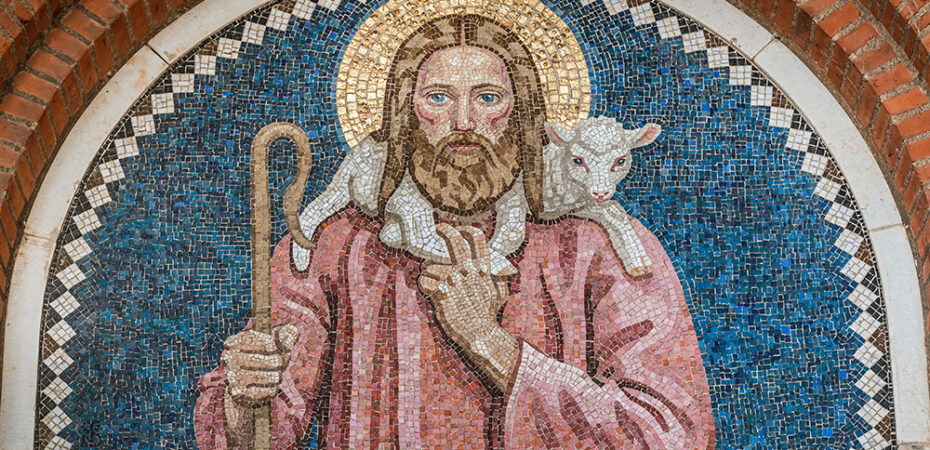

Still, these awe-inspiring portraits of Christ were balanced, to some extent, by some softer, more human, gentler images of Jesus. Jesus with the children, for example. Jesus, the Sacred Heart, looking out at us in that uniquely welcoming, loving way. And Jesus the Good Shepherd. I was especially attracted to that one, the picture of a simpler, roughly clad man with a sheep thrown over his broad shoulders. I could almost hear the sheep bleating with delight.

Perhaps it was my own fondness for animals that made this image seem so accessible and real. We always had a family dog. I used to tease my parents that I was named after Mike, the toy fox terrier who was already pampered by the family. Then there was Joey, a Lab mix, my best buddy. I loved to stroke his thick, black coat. We used to take walks together in a nearby park and watch birds, squirrels, rabbits, kids and sunsets. Perhaps I sensed that Jesus’ love for me was something like my care for that pet.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

The Good Shepherd and the Gate

“‘Amen, amen, I say to you, whoever does not enter a sheepfold through the gate but climbs over elsewhere is a thief and a robber. But whoever enters through the gate is the shepherd of the sheep. The gatekeeper opens it for him, and the sheep hear his voice, as he calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. When he has driven out all his own, he walks ahead of them, and the sheep follow him, because they recognize his voice. But they will not follow a stranger; they will run away from him, because they do not recognize the voice of strangers.”…

Jesus said again, ‘Amen, amen, I say to you, I am the gate for the sheep. All who came [before me] are thieves and robbers, but the sheep did not listen to them. I am the gate. Whoever enters through me will be saved, and will come in and go out and find pasture. A thief comes only to steal and slaughter and destroy; I came so that they might have life and have it more abundantly. I am the good shepherd. A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.’” — John 10:1-11

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

“I am the good shepherd” (Jn 10:11). John devotes most of Chapter 10 of his Gospel to this image. Probably no image of Jesus has more sentimental appeal or more warm reassurance than the picture of the smiling Savior holding a tiny lamb close, or on his shoulders, or striding through a lush meadow surrounded by his flock. After all, who of us doesn’t long to hand over our lives, with their troublesome decisions and challenges, to the care of one who will guide and protect us with such tenderness? We just have to listen for his voice and go where he goes.

However, I was well into adulthood before someone pointed out to me that this is not the most flattering image Jesus might have chosen for us! Sheep are not very smart and not very brave. They’re dirty and smelly. They tend to wander aimlessly, requiring constant attention. They can be stolen without much protest, and they’re easy prey for wild animals like wolves who are faster, more aggressive and more cunning.

Exposed to wind and weather, tending the sheep was considered odious work. Shepherds of Jesus’ time were scorned and made the butt of jokes by city people. They had the reputation of being rough, unwashed characters, often lumped together with tax collectors, prostitutes, roadside robbers and others regarded as undesirable or suspicious. Yet, curiously, it was shepherds who attended his birth, and it was these very sorts of people whom Jesus sought out and befriended. So it’s remarkable that John’s Jesus actually identifies himself with these marginal people.

I’ve learned about how shepherds in Jesus’ day sometimes worked together. In the daytime, they would graze their flocks in separate pastures, but at night they would gather in a single enclosure for protection from bandits and wolves. Within the enclosure, the sheep would get all mixed up. Then, in the morning each shepherd would call his sheep, and even though sheep aren’t very smart, they get to know their shepherd’s voice and will follow only that person.

More recently, one of my students taught me something else. Sometimes at night, the shepherd would actually lay down across the opening in the enclosure, literally making himself the gate, keeping the restless sheep in, and predators and thieves out.

For me, this sheds new light on Jesus saying, “I am the gate for the sheep” (Jn 10:7). Now we have a picture of someone who throws his body between us and the threats to our lives. Now we have an image of a Savior who puts his own life at risk for the skittish and often thankless members of his flock. Shepherding is more than a kind disposition: it’s a dangerous business.

Confronting Danger

We’re called to be shepherds after the model of the Good Shepherd. If someone would suffer for me, stand guard for me, fending off the wolves and thieves who would carry me away, for whom and for what would I do such a thing? Where might I lay myself down, that others might live?

We’re in the wrong line of work if we think this task can be performed at a distance, in sanitary safety, without risk. Priestly ministry is in the very business of routing evil and confronting danger.

Pope Francis surely saw this when he gave us the arresting image of being shepherds “with the smell of the sheep.” We are bonded with a flock, and life dirties all of us. And that is precisely where the Good Shepherd comes to find us.

Let’s be honest here: it’s tough to be a shepherd. No, I’m not talking about the low market price for wool or lamb chops. I’m thinking rather of those who lead us in the Church, in government, in our educational and commercial institutions, even moms and dads who must guide and protect their little flocks. We’ve been rocked by scandals, some of them very close to home. We’ve suffered disappointment after disappointment in those who are supposed to be looking out for the good of the whole flock, but who instead put their own pleasure or gain ahead of the interests of those they serve.

Maybe, like me, you’re left scratching your head and wondering, what does it all mean? Where is God in the middle of this mess? Is there any leader we can trust? And what will it mean for me to be called to leadership?

Willingness to Be Led

But while sheep may want a shepherd to guide, pasture and take care of them, I’m not sure I do. In other words, I think there is an even more basic problem in approaching this image, and it is our resistance to being led, our blindness to being connected with others and with God, our denial of our need for anybody or anything outside of ourselves.

Our culture has a basic text, a narrative, which every American is given at birth. It has many expressions, but here is a stark one which comes from Ayn Rand: “I swear … that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.” The American narrative is one of “rugged individualism,” the Lone Ranger who meets the world on his or her own terms, who does it “My Way” (thank you, Frank Sinatra), who defines herself/himself without any constraints, preconditions or commitments.

Think of how many times we have all heard the saying, “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps.” Did you know that when that expression was coined, it was used in a derogatory way? It’s an example of something which is patent — even laughably — impossible because it defies the laws of physics. We have converted a foolish and delusional thought into an ideal or virtue, and laid it upon others, like the poor, as an imperative.

The image of a sheep captures one essential thing: We are creatures, dependent beings. We cannot make ourselves, we cannot save ourselves, we cannot pull ourselves up by our own virtue or accomplishments. And it’s a good thing, too.

I’ve had some health problems recently. To be seriously ill, even temporarily, collides headlong with your illusions of independence or self-sufficiency. It challenges you to accept personal limitations, to welcome the help and care of others, and to set aside all you previously regarded as so very important. I’ve had several brief hospital stays, and I must say, whether it was doctors, nurses, CNAs or the staff who came to pick up my garbage, I was treated almost unanimously with care and attentiveness.

It was the nurses, however, who made the deepest impression on me. They never treated me condescendingly, as an object of pity. They would talk with me as if I was a real person and not just a bother or a package of tasks they were assigned to do. They also didn’t pamper me; they would insist that I do what I could for myself, understanding that that too is part of the healing process.

Lately, I’ve been thinking that we should just hand the world over to nurses and first responders of all kinds. Why? Because they get it. They understand that we’re all in this together, that we’re all dependent and weak and there is no shame in that, and that living for others, tending to one another’s wounds and needs can be a beautiful, ennobling way of life. They made me think in a fresh way about Pope Francis’ call for the Church to be a “field hospital.” Maybe they can show us the way.

So the basic question for us and our flock is, Will we be led at all? Our culture emphasizes individual agency to the max, and this thinking even finds its way into popular versions of spirituality. Again and again, it seems to me our fundamental challenge is simply to accept our creaturehood. We don’t like to be needy and admit we don’t always know the way. But that is who we are: contingent, dependent — and graced — creatures.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

‘I Will Give You Shepherds’

In Pope St. John Paul II’s post-apostolic exhortation Pastores Dabo Vobis (“I Will Give You Shepherds”), he writes: “God promises the Church not just any sort of shepherds, but shepherds ‘after his own heart.’ And God’s ‘heart’ has revealed itself to us fully in the heart of Christ the good shepherd. Christ’s heart continues today to have compassion for the multitudes and to give them the bread of truth, the bread of love, the bread of life (cf. Mk 6:30ff.), and it pleads to be allowed to beat in other hearts — priests’ hearts: ‘You give them something to eat’ (Mk 6:37). People need to come out of their anonymity and fear. They need to be known and called by name, to walk in safety, along the paths of life, to be found again if they have become lost, to be loved, to receive salvation as the supreme gift of God’s love. All this is done by Jesus, the good shepherd — by himself and by his priests with him.” — No. 82

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Going Somewhere

Our too often sentimentalized view of the Good Shepherd could result in a too passive view of Jesus and, hence, a too passive view of our role as pastoral leaders. We may overlook the fact that shepherding is not sit-around time. No, shepherds are paid and appointed to lead the flock; to know where good, reliable pasture and water may be found; and how to avoid cliffs, mudholes and predators. They are to keep the flock together, corralling the wandering — no small thing in itself — and, when necessary, showing them the way to better, safer, saner living.

I once heard a homily or retreat talk about how shepherds routinely lead “from behind” — that is to say, they follow along behind the flock, yielding to the animals’ sense of where they should go. I don’t know what the truth of this may be in terms of ancient shepherding practice, yet the speaker did make a point worth considering. But, as happens so often with a valid point, it seems to me that if pressed too far this metaphor leaves something important behind. After all, the shepherd is hired for his knowledge and prudence, which might surpass that of the sheep at times. The shepherd is not infallible, of course. But the shepherd should know the needs of the sheep well enough, and know the landscape well enough, to be able to see when it’s time to move on to another place.

As collaborators with the Good Shepherd, do we lead from in front or from behind? I say it’s both. There are times when those in our care will know better than we do, and we have to be humble enough to recognize their gifts and let them play their leadership role. Conversely, there are times when we will need to assertively take the lead and persuade them to follow. Either way, we have to be habitual, well-practiced listeners. We need to listen to Jesus himself, of course — more on that in a moment. But we also need to listen to our people. The kind of listening I mean here is long, hard, deep — and joyful. We do it so that we can understand folks’ needs, hopes, dreams, struggles and sorrows. We also do it because the Good Shepherd will himself speak to us most often through others.

My default mode tends to be to think of myself as a companion amid the flock. But I’m aware that pastoral authority is given for the good of the flock, and there will be moments for me to challenge or present a bigger vision. Good shepherds do not dominate. They do not over-rely on the power of office. They do not bark orders nor moralize. They recognize, willingly embrace and rejoice in the other gifts around them. Collaboration is their daily bread and butter. But they realize that shepherding after the heart of the Good Shepherd is not static; it means being on the move, on the way somewhere together.

This might be a good moment for each of us to ask ourselves: Are we going somewhere? Where? What are we hearing from and through our flock? What vision do we have not only for our own work as priests but for the spiritual progress of our community? This is the heart of what our presbyteral vocation means: true spiritual leadership, the kind of leadership to bring people into an authentic, experienced encounter with the Lord, the kind of encounter that draws them into committed, intentional, missionary discipleship. We do this through our preaching, our counsel, our committee meetings, our stewardship and our nurturing of the bonds of community.

Discerning His Voice

Shepherding, then, is a ministry of discernment. We are the Church’s local leaders in the necessary, life-giving task of helping everyone to know and heed the Good Shepherd’s voice. Indeed, this may be our most important role. For example, when we lead liturgical prayer, our call is not merely to invite people to hear the Scripture readings, much less to hear us in our preaching. Both of those — biblical texts and homily — are privileged means toward the larger end of hearing the Shepherd’s voice speaking to us today.

Christian faith preserves a treasury of past events and insights, found in texts, memories and institutional continuity. But we do this precisely because we are fundamentally a religion of a living God, a God who speaks and acts and moves and accompanies as surely today as in ages past. The past is a guide to the present, and both past and present strain toward the future. We must be skilled in the art of knowing Jesus’ voice and presence among us now. This is a formidable challenge.

One time several years ago, I picked up the phone to call my parents. I dialed the number, waited and heard it start to ring. Then a strange thing happened. Suddenly something went haywire on the line, and I started hearing all these voices, dozens of voices. But after several seconds of this cacophony, I could hear distantly the voice of my mom answering the line — “Hello” — in the way only she could do. Her voice was not louder than the rest, but I knew her voice for so many years that above all those other voices my ear instantly picked hers out of this crowd. This experience reminds me of what is said about the mothers of young children: They know the unique sound of their kid crying, even across a crowded supermarket.

Those few weird seconds on the phone are symbolic to me of our situation in life. There are gazillions of voices calling out to us in one way or another. Some are reassuring, some frightening, familiar or strange, enticing or repulsive. They can be friends, family, authority figures, politicians, people selling us stuff, people in need. Some are supremely memorable. I can still hear the sound of my grandmother laughing, even though she has been dead for nearly 40 years.

But the voices do not always agree, and therein lies much of life’s tension and a good bit of our ministry as priests. Jesus says, “My sheep hear my voice; I know them, and they follow me. I give them eternal life” (Jn 10:27-28). We can easily be confused by all the voices we hear. Again and again, we hear various forms of this confusion from those under our care, not to mention from our society at large.

We have to know the voice of our Shepherd when he calls so that we can assist our brothers and sisters in the same daily discernment. There is only one way to learn what the voice of Jesus sounds like, and that is to practice listening to it. Sometimes, this means shutting out other voices, the way we do when we study or set aside time to pray and reflect. We have to depend on one another, too, for help in distinguishing the voice of Jesus: This is why Christian community is so important.

Our annual retreat plays a crucial role in continuing to deepen our ability to recognize and submit to the Good Shepherd’s leadership. On retreat, we dedicate time just for this purpose: to spend time with him, listening deeply for his voice. Retreat is nonutilitarian time: We don’t pray to get something, release tension or write our next homily. No, we go on retreat to let Jesus tend to our souls. How fortunate we are that the Church affords us this time and so many beautiful, quiet places in which to spend it.

“I give them eternal life, and they shall never perish” (Jn 10:28). This is not a promise of an easy life in this world. It is a promise of something that the world cannot give us: call it an inner life, a deep-down serenity, energy, and direction which nothing can take from us and which we believe will never end. It is a promise for us, and for the flock we tend.

FATHER MICHAEL E. CONNORS, CSC, is a pastoral theologian in the theology department at the University of Notre Dame and director of the John S. Marten Program in Homiletics and Liturgics.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

World Day of Prayer for Vocations

The 59th anniversary of the World Day of Prayer for Vocations is May 8. The U.S. bishops explain that the “purpose of World Day of Prayer for Vocations is to publicly fulfill the Lord’s instruction to, ‘Pray the Lord of the harvest to send laborers into his harvest’ (Mt 9:38; Lk 10:2). As a climax to a prayer that is continually offered throughout the Church, it affirms the primacy of faith and grace in all that concerns vocations to the priesthood and to the consecrated life. While appreciating all vocations, the Church concentrates its attention this day on vocations to the ordained ministries (priesthood and diaconate), consecrated life in all its forms (male and female religious life, societies of apostolic life, consecrated virginity), secular institutes in their diversity of services and membership, and to the missionary life.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………