An Oxymoronic Church?

The Church changes, only so that it can remain the same

Father Patrick Manning Comments Off on An Oxymoronic Church?

St. John Henry Newman is often attributed to the quote, “To live is to change, and to live well is to have changed often.” Despite our almost innate resistance to change (which we often experience as disruptive, at best), change is the only constant and trustworthy sign of life. Every living organism testifies to change as evidence of vitality (as the seed hardly resembles the full-grown plant).

In high school, I remember bragging that I knew the meaning of the curious word oxymoron (a juxtaposition of seemingly opposing words that ostensibly are self-contradictory, but which becomes a useful rhetorical device to make a point — for example, “bittersweet,” or a “brawling love,” as we find in Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet”).

The Church, a living organism energized and guided by the Holy Spirit, has always, in some sense, changed — but herein is found the oxymoronic nature of the Church: The Church has always changed, only so that it can remain the same. That is, charged with spreading the Good News, and with it truths that can never change (dogma), the Church has to change as fast as it is able just to remain the same. If the Church wants to be what it has always been and wishes to do what it has always done, it will have to change so that it can remain true to its charge.

A helpful analogy might be the task of the owner of a store that has always been the local No. 1 store in fashion. It has been this way and certainly wants to remain the same — be No .1, the forefront of fashion. The owner has to consistently change the front windows and the store’s inventory — only to remain the same.

Constancy and Change

St. Paul had to change his methods of preaching in many circumstances so that he could be true to the unchanging truths of Christianity. He employed, good Pharisee that he was, passages from the Hebrew Scriptures when he preached Jesus to the Jews. Such references would be of little use to him when he preached to the Greeks in Athens and onto the Acropolis.

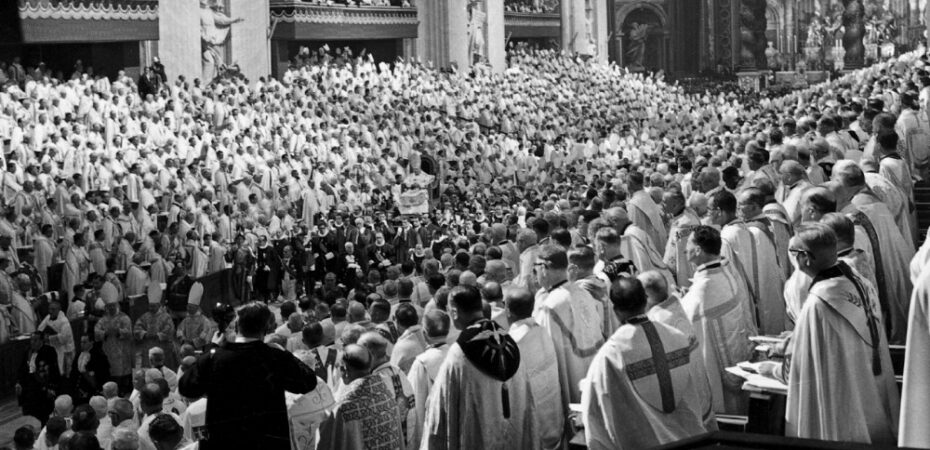

The Church looked very different in the time of St. Augustine in northern Africa than it did to Cardinal Newman in mid-Victorian England. The Church looked very different during the time of Emperor Constantine than it did at the time of the Council of Trent. The Church in Nigeria looks quite different in the present than it does in the United States of America. But it is the same Church, with the same unchanging dogmas and teachings. The Church has to look different because it is preaching to different people in different times, places, circumstances and cultures.

We need only to look at the difference between Paul’s letters. In his earliest letter, he is addressing the fears of those who had loved ones who died and were concerned that Jesus had not yet returned as promised (cf. 1 Thes 4:13). In his First Letter to the Corinthians, the issues that needed to be addressed were divisions in the community and misbehavior at the Eucharist.

When you see a picture of yourself at 3 years old, then 10, 17 and 30 (and onward), you do not look the same at all because you have grown and changed. But, in essence, you are the same; and the same is true for the Church.

In a parallel way, if one wants to be the best parent one could be, he or she will have to change (often, perhaps) to remain the same — that is, to be the best parent possible. One cannot parent a child at 18 years of age as he or she did when the child was 3.

The need to change to remain the same holds true in most facets of life — whether trying to be the best friend, neighbor, employee, employer, teacher, spouse, etc. To be what we have always been, and to do what we have always done, we will have to change.

Christmas is always Christmas. For the secular person, it is Dec. 25; for the Christian, it is the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. But no adult embraces Christmas when he or she is 70 as he or she did when they were 7.

In a matter of a few days, I had an early morning Mass at a long-term care facility. Then I spent the whole day teaching freshmen religion at a Catholic high school. Then, in the evening, I taught my theology course at a local Catholic college. Then, on the weekend, I celebrated the liturgy at a local parish. In all of these circumstances, I did the same thing — I talked about the Lord Jesus. But to do so effectively I had to change because the circumstances were different … just as the circumstances in the Catholic Church, today are different than they once were.

Latin

There is much talk today in the Catholic Church about Latin, a language I love and the class that was my favorite in the seminary. But to the point of this essay, many do not understand that the only constant in life (and so in some of the externals of the Church) is change. There is the seminarian who wants Mass in Latin, “Like it always was.” Is that so? When asked if he recognized the words Kyrie Eleison, he said certainly, that is part of the Latin liturgy.

Fair enough, one could answer, but it is not Latin at all — it is Greek. The language of the Roman Empire at the time of the apostles was Greek (ergo the language in which the New Testament is written), and thus the liturgy was celebrated in Greek before it was so in Latin. The Latin language took over the Roman Empire long after the apostles. But the truth is, if one wants to celebrate the liturgy as it was “in the old days,” then one would have to learn Aramaic, for this is the language in which Jesus spoke and prayed.

Embracing Change

One of the great blessings of the Roman Catholic Tradition (intentional upper case “T”) is that we see no opposition between faith and reason, between religion and science — a gift for which we ought to thank God daily.

We Catholics are able to embrace changes learned from the psychosocial sciences and yet never have any of the content of our faith threatened. One example that I might offer is that, in the past, the Church (understandably, at the time) deemed the tragedy of suicide a mortal sin. But learning from psychology, we changed our thoughts on this. How and why? Well, the three criteria for a mortal sin would be: a serious matter; knowledge of the gravity of the matter; and freely choosing it. It is on this third point that psychology challenges what we had thought.

Psychologists tell us that the tragedy of suicide, in most instances, is not freely chosen, often because of the incredible pain in which the person finds him or herself. And thus, if such a painful and tragic occurrence is not necessarily freely chosen, then it cannot, by one of the Church’s own criterion, be a mortal sin. Pastorally, this is so important for the families of those whose lives have been devastated by this painful experience of losing a loved one so tragically.

Another example of the Church embracing change is founded on the Church’s conviction that creation is still good, if flawed. So that we can say, in general, that language, alcohol, drugs, money, sex, even religion are, in essence, good. What gives them their moral value (or disvalue) is human agency. To add some red wine to a recipe is a wonderful use of alcohol; to drive a car under its influence is categorically immoral.

So, too, then, with social media. It can be a wonderful tool for spreading the Gospel, though it can also be misused — but again, the issue is not social media, but its (mis)use by human beings. That is why we have Catholic radio and television, podcasts and Catholic websites, parish websites and Facebook accounts — one vocation director told me he would be completely out of the game if he did not have access to social media (which allows him impactful access to young people).

So change abounds — we have fewer (and older) priests, and fewer (but I suggest braver) vocations. We have parishes merging and some church buildings closing. Bishops and pastors have to make decisions that people find disruptive.

True, the Church does not look like it used to look. But, guess what? — it never did. It never looked like it used to look, and it is not supposed to. This is a sign that the Church is a living organism, empowered by the Holy Spirit. And we have the promise of the Lord Jesus to be with his Church until the end of time. He would not have said it if he did not mean it — and this is a promise that will never change.

FATHER PATRICK MANNING, Ph.D., is a priest of the Diocese of Youngstown, Ohio.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The Temptation of Complacency

When Pope Francis addressed the faithful for the opening of the synodal process on Oct. 9, 2021, for the world Synod on Synodality, he spoke about the temptation of complacency, “the attitude that says: ‘We have always done it this way’ (Evangelii Gaudium, 33) and it is better not to change. That expression — ‘We have always done it that way’ — is poison for the life of the Church. Those who think this way, perhaps without even realizing it, make the mistake of not taking seriously the times in which we are living. The danger, in the end, is to apply old solutions to new problems. A patch of rough cloth that ends up creating a worse tear (cf. Mt 9:16). It is important that the synodal process be exactly this: a process of becoming, a process that involves the local churches, in different phases and from the bottom up, in an exciting and engaging effort that can forge a style of communion and participation directed to mission.

“And so, brothers and sisters, let us experience this moment of encounter, listening and reflection as a season of grace that, in the joy of the Gospel, allows us to recognize at least three opportunities.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..