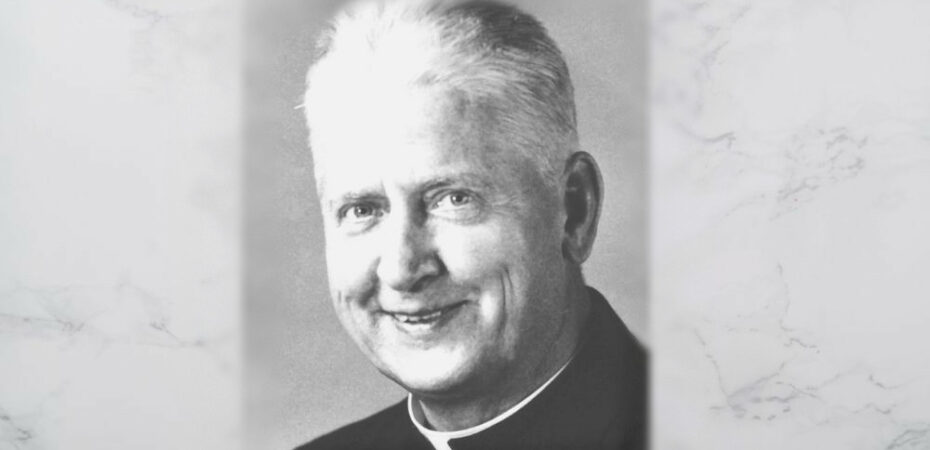

A Priestly Priest

The exemplary life of Father Walter Ciszek, SJ

Susan Muto Comments Off on A Priestly Priest

In his famous book, “He Leadeth Me: An Extraordinary Testament of Faith” (Image, $16), Father Walter J. Ciszek admits that in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, the town of his birth on Nov. 4, 1904, the neighbors called him tough, stubborn and incorrigible, and wondered what would become of him. Young Walter took no pride in his demeanor, saying only that it served to reveal the raw material with which God had to work!

He picked most skirmishes just for devilment. He liked his school not so much for learning but because it had a playground where he could fight with anyone who crossed him. While he was still in grammar school, his father took him to the police station, insisting that he be sent to a reform school.

Any plan God had for his life seemed to be in disarray until he finished school, listened to good advice and decided, at the age of 24, to enter the Society of Jesus. In the second year of his novitiate, the general of the Jesuit order invited future priests to volunteer to enter the then-Soviet Union. In 1930 he took final vows, followed in 1934 by theological study at the Gregorian University in Rome, where he also began his study of the Russian language.

On June 23, 1937, he was ordained in Rome and shortly thereafter volunteered to enter Poland. In 1938 the American Embassy warned all citizens to leave that country due to the imminent arrival of the Germans and Russians. However, on March 19, 1940, on the feast of St. Joseph, Father Ciszek entered the former USSR. Less than a year later he was arrested by the KGB, the former Russian secret police and intelligence agency, and accused of being a suspected spy. He was jailed immediately and later that year transferred to Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. On July 26, 1942, he signed a “forced” confession and was detained at Lubyanka until 1946. Having refused to be a counterspy, he was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor in Siberia and transported forthwith to a Siberian prison camp in the Arctic Circle.

By 1947 he was presumed dead by the Jesuits in the United States, but, miraculously, on April 22, 1955, he was released from prison after 14 years and 9 months. As a convicted spy, he had to remain in Russia on a restricted passport. Two years later, in 1957, the KGB warned him to stop all priestly ministry, but in April 1958 he celebrated a glorious Easter despite opposition.

In the summer of 1959 the American Embassy helped him obtain an exit visa. On Oct. 3, 1963, he departed from Russia and a few days later, on Oct. 12, 1963, he arrived in America. A year later, he published with co-author Father Daniel Flaherty, SJ, “With God in Russia,” and in 1973, aided by the same co-author, he released “He Leadeth Me.” For the next 10 years he engaged in the work of spiritual direction at the retreat house of the Jesuits in New York City. On Dec. 8, 1984, on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, he entered eternity. His cause for canonization is in process.

Learning in Lubyanka

Father Ciszek admits that the first lesson Lubyanka taught him was that he had never really abandoned himself fully to the mystery of God’s mercy. He thanked God perfunctorily while still clinging to the illusion that he could manage his own life. It took him many years of meditating on the Lord’s Prayer to obey the Father’s will. Whether he succeeded or failed was God’s business, not his. What mattered was to believe that God was with him in every detail of his life: before, during and after his imprisonment. Trust in God would save him and show him his ultimate purpose in life.

When he was first imprisoned, a sinking feeling of helplessness and powerlessness overcame him. He could not believe he lost control of his life. He felt completely cut off from everything and everyone who might conceivably help him (see “He Leadeth Me,” Page 45). Being accused of spying broke him in body and spirit. Because there was no one to whom he could turn, Walter “turned to God in prayer” (Page 48).

Old character traits like stubbornness gave way to his becoming more docile and acutely aware of God’s patience with him. He had to become a more patient pupil of God. Self-control was not enough to overcome his struggles with depression, fear and insecurity. The feeling he sought was contingent on the depth of his personal relationship with God and the quality of his prayer life. It had been finely honed from an early age by his love for the Eucharist and his own devotional practices.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

CAUSE FOR CANONIZATION

“Almost immediately after his death, a petition to recognize his heroic virtues and outstanding holiness was circulated by Mother Marjia, the superior of the Byzantine Carmelite monastery Father Ciszek had helped to found. Five years later Bishop Michael J. Dudick began the official diocesan process of investigation for the Eparchy of Passaic and the Father Walter Ciszek Prayer League was formally incorporated as the Official Organization for the Promotion of the Cause of Canonization of Father Walter Ciszek. With the arrival of Bishop Andrew Pataki as the head of the Eparchy of Passaic, the cause was transferred to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Allentown (in which see Shenandoah is located).”

— Father Walter Ciszek Prayer League, ciszek.org

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

In Lubyanka, God initiated in Walter a slow but steady conversion experience that lasted a lifetime. Unceasing prayer countered loneliness, confusion and a sense of worthlessness; it enabled him to suffer patiently; it was a prerequisite for his finding that the grace of faith, given in the present moment, was enough for him to endure whatever crosses God asked him to bear.

The purification he underwent drew him from the “midnight” moments of sensual deprivation and feelings of spiritual abandonment to the dawning light of a new day of faith and prayer, moving him from reliance on his own willpower to doing God’s will.

During his first year in Lubyanka, he “underwent a purging” of self that left him “cleansed to the bone.” There was only one reality there — the “total and all-pervading silence that seemed to close in around [him] and threaten [him] constantly” (“He Leadeth Me,” Page 55).

For a while he lost hope and even questioned his faith in God, until he returned to a special devotion to Our Lord’s agony in the garden. In the silence of his cell he began to realize the power of God’s grace working within in the concrete circumstances in which he found himself. He knew from experience that the interrogators of Lubyanka were exteriorly kind but interiorly deceptive.

He recalled the alarming truth that the devil took on the appearance of an angel of light while causing nothing but more deceit and confusion. He had to discern God’s call at the core of his being to counter the temptation to absent himself from recollection. Memory served to remind him of the discernment of spirits taught by St. Ignatius of Loyola. It became the eye of his body and the lamp of his soul.

During his last four years in Lubyanka, Our Lord continued fine-tuning Walter’s soul. His time there gave him the courage to trust totally in Divine Providence and to appreciate the Lord’s love for him, no matter how worthless he felt. Once he began to order his life according to the proclamations and petitions found in the Lord’s Prayer, he began to rise “from the tomb of Lubyanka” and to appreciate anew the words: “Behold I send you as sheep in the midst of wolves.”

Lubyanka was in many ways like his Jesuit novitiate experience in which he was “alone with God as it were on the mountaintop” and able to develop the habit of recollection (see “He Leadeth Me,” Page 90). He rediscovered the need to listen to the interior voice of conscience and to discern God’s will in every situation. He learned to act not on his own initiative, but in response to whatever demands were imposed by God in the concrete instances of each day. Best of all, he sifted through the inner movements of his heart rather than feeling trapped by any calculated method to gain control.

Priest-Servant; Priest-Victim

Father Ciszek saw himself as being liberated even while in prison. He would be a priest-servant to everyone for whom Jesus died on the cross. For all the hardships and sufferings he endured, the prison camps of Siberia held one great consolation: He was able to function as a priest again. He could offer Mass, although in secret, hear confessions, baptize, comfort the sick and minister to the dying. He was able to instruct new listeners in the Faith and strengthen those whose faith was weak. He understood what it was like to be a believer in name only and yet to hunger for more. As a priest-servant, his life was poured out like a libation for the spiritual good of his brothers and sisters in Christ. Day and night, when anyone came to him for help or counsel, he was always ready to address their needs.

Father Ciszek was also a priest-victim, sharing with Jesus the mystery of redemption. To prepare him for this apostolate, God allowed him to spend five years in solitary confinement. He endured the humiliations of a lack of privacy, being watched day and night; he was tempted by prostitutes who were sent to try to lead him into sin; he underwent trials of constant interrogations; he suffered hunger and, above all, a profound sense of loneliness that almost caused him to lose his faith.

In addition, during the 15 years he spent in the labor camps in Siberia he was under constant surveillance, threatened by informers, deprived of privileges that he had actually earned simply because he was a priest, given meager food and, above all, harassed when he attempted to say Mass.

Father Ciszek endured all of these sufferings, dying to himself to become a servant and a victim with Christ that others might live. He considered saying daily Mass in the Soviet Union his most important act. It compensated for all the sufferings and hardships he had to undergo in this desolate country that deprived its people of religion and God. Just to be able to bring God to people in a place where the Church and the priests were openly persecuted made him feel what a true calling to the priesthood demanded from those who were chosen, called and committed to be true disciples of Christ.

The hope flowing from the empty tomb gave Father Ciszek the courage, as well as the joy, to persevere, even when he saw few fruits of his labor. His life became like a eucharist of everydayness. He had learned to love the Mass from his earliest youth. As a youngster, attending Mass with his mother especially impressed him. She often repeated to him the words of the consecration, telling him to remember that after the priest pronounced, “This is my body,” Our Lord descended upon the altar in a mysterious way and remained present there until he was received by the faithful in Communion. For reasons that deepened with each passing day, he never questioned the truth of the words of the consecration; he accepted at face value what they signified. As a result of this belief, he developed a deep reverence for the Eucharist and a respect for the churches in which the Blessed Sacrament was reserved.

As the years passed, this interim feeling of reverence for Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament increased, together with his respect for the priests who celebrated the Mass and devoted their lives to serve God as custodians of this august Sacrament.

After his release from prison and his return to the United States, he spent the rest of his life sharing the spiritual treasures he had received in Russia with the People of God. He did so in his priestly work of spiritual direction, in his inspired writings and, above all, in the ministry of becoming with Jesus a witness to the efficacy of absolute trust in Divine Providence.

SUSAN MUTO, Ph.D., is dean of the Epiphany Academy of Formative Spirituality in Pittsburgh and author of “Gratefulness: The Habit of a Grace-Filled Life” (Ave Maria Press, $16.95).

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Will of the Father

Father Walter Ciszek, in “He Leadeth Me,” writes: “My life, like Christ’s — if my priesthood meant anything — was to do always the will of the Father. It was humility I needed: the grace to realize my position before God — not just in times when things were going well, but more so in times of doubt and disappointment when things were not going the way I would have planned them or wished them. That’s what humility means — learning to accept disappointments and even defeat as God-sent, learning to persevere and carry on with peace of heart and confidence in God, secure in the knowledge that something worthwhile is being accomplished precisely because God’s will is at work in our life and we are doing our best to accept and follow it” (Page 185).

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………