Pope Gregory XV (r. 1621-23)

The programs he implemented have impacted the Church for 400 years

D.D. Emmons Comments Off on Pope Gregory XV (r. 1621-23)

Often slighted by Church historians, Pope Gregory XV, who died 400 years ago this year, had a remarkable reign while on the Chair of Peter. Although he was pope from only 1621 until his death in 1623, the programs he implemented have impacted both the Church and the faithful of every generation.

Alessandro Ludovisi, who would take the name Gregory XV, was not the first choice of the cardinals voting in the papal conclave of 1621. In fact, he was a compromise candidate, elected by popular acclaim in less than 24 hours.

At the time of his election, he was 67 years old, significantly old in 1621. He was also sickly, suffering from severe stomach ailments, and because of health issues his colleagues considered him a short-term pope, a kind of transitional pontiff. Indeed, he would live less than three years after being elected, but he did not simply fill a role or just act as a figurehead. His achievements were essential to the continued role of the Church in salvation history.

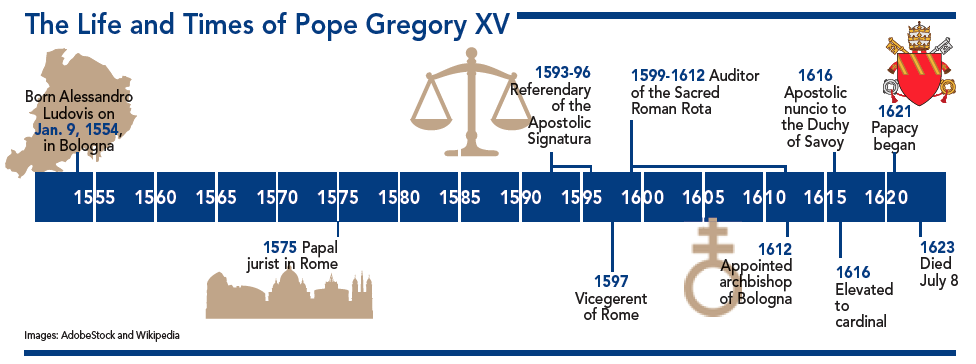

Born in Bologna, Italy, on Jan. 9, 1554, Ludovisi was educated by the newly formed Jesuits (the first pope trained by Jesuits) and then went on to study law and earn a degree in both canon and civil law. In 1593, he was called to Rome by the Holy See to serve as a senior judge in the Church’s court. He exhibited an impressive judicial mind and was highly regarded for his fairness and wise judgments. These attributes were noticeable by those around him and he was selected as a Vatican diplomat, ambassador, nuncio, problem solver — all in all, a peacemaker. He was instrumental in settling controversies between the Vatican and various secular governments, as well as intervening and resolving difficulties between warring nations.

Selected as the archbishop of Bologna in 1612, there is no evidence that he was ordained until he became archbishop. In 1616, he was proclaimed a cardinal by Pope Paul V (r. 1605-21). As the 234th pope, the programs Gregory XV instituted would resolve critical issues both inside and outside the Vatican.

Church Reforms/Missionary Work

Gregory’s papacy took place less than 60 years after the end of the Council of Trent (1545-63) and at a time when the reforms of that council were still being sorted out and implemented across the Church. The council and the subsequent reforms, some long overdue, were in response to the Protestant Reformation, which had caused millions of Catholics to split from the Church, a period regarded by many as the greatest crisis in Church history. Pope Gregory’s reign was part of the continuing Catholic Counter-Reformation, seeking to bring defectors, the strayed sheep, back to the fold, back to the Church Jesus founded. Thus there was a need to go into countries throughout Europe seeking the return of those who had fallen away, to recapture their souls. Convincing people that they had been led astray and that the Church was indeed addressing acknowledged and needed reforms was not an easy task. This had to be done in a dogmatic, well-orchestrated way, including the use of Church representatives and missionaries to carry out such an assignment.

Gregory recognized that one way to return those who had chosen to hear another voice was to gain confidence and develop a relationship with the heads of the different countries where Protestantism had prevailed. Such an effort was especially challenging as many of the monarchs in those locations wanted access to the riches of the Catholic Church.

Ever a diplomat and guided by the Holy Spirit, Pope Gregory used personal involvement, funding, dispatch of papal legates, missionaries, and even the use of military force in successfully gaining and regaining Catholic influence in various countries. This was the time of the Thirty Years War, during which some 30 million people were killed, largely over what religious practices a people would follow. Every country in Europe was impacted. Gregory reigned against the backdrop of Catholics and Protestants killing one another, thus every success came during trying times. At the forefront of this Counter-Reformation were the numerous Church-recognized religious groups that were effectively carrying both the Gospel message and the reforms to the many locations where Protestants had gained a foothold.

But such missionary campaigns were not limited to the European continent. This was the time of continued exploration of the New World and the discovery of new peoples. Protestant missionaries were certainly interested in converting the native populace to Christianity using the teachings of Martin Luther. The 17th-century Catholic Church then had not only to reform those who had separated from the Church, but to also bring the true teachings of Jesus to newfound people.

To better facilitate this God-given missionary responsibility, Pope Gregory issued his papal bull Inscrutabili Divinae Providentiae Arcano (1622) establishing the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. The intent was the creation of an organization to effectively coordinate Catholic missionary activity all over the world, and assuming control of the missionary process from various entities, including state governments. Previously, different countries each had their own missionaries and different ways of schooling or preparing individuals for roles as Christian evangelists. In sum, there was little commonality among nations, and the national interest of each country sometimes outweighed the needs of the Church.

Bringing the missionary role under the papacy, through the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, is a method that is still in place today. The congregation reported directly to the pope. Part of the success of this endeavor was the growth and influence of several religious groups that Gregory supported, including the Jesuits, the Carmelites and the Oratorians, all of which flourished in the mid-17th century. These groups and others were instrumental in affecting reforms within the Church, explaining the reforms to those who had separated and gone over to Protestantism; some had great success in bringing Jesus Christ to Natives in distant lands. Religious orders and societies remain in our time at the center of Catholic missions around the world. The methodology implemented by Gregory has been fine-tuned and carried on to today under the Vatican’s Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. Interestingly, this congregation reports directly to the pope much like its predecessor did in 1622.

On March 12, 1622, Pope Gregory canonized four key figures that were instrumental in the Church reform and missionary effort: St. Teresa of Ávila (1515-82), St. Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556), St. Francis Xavier (1506-52) and St. Philip Neri (1515-95). Selection of these individuals for sainthood (plus St. Isidore the Farmer, 1070-1130) included the step of beatification, which until that time was not part of the canonization process. Called the great canonization, this was the first time multiple people were canonized on the same day. By this act, Pope Gregory elevated and further legitimized the status of the religious orders these new saints represented and recognized the essential role they played in the life of the Church.

Papal Election Process

Into the 17th century, the papal election process was greatly abused. Cardinals were pressured by heads of governments, high-ranking states, even Church officials to favor one papal candidate over another. The idea was to put their preferred choice on the Chair of Peter, expecting favors in return. Simply put, royalty meddled in the papal election process trying to sway the vote of the cardinal electors. Oftentimes, debate over who should be elected took place even before the incumbent died. Gregory, with the support of many cardinals, took action to end such manipulations by requiring all voting to commence only after the conclave was closed to the outside world, and required such voting be done by secret ballot. Cardinals could vote for only one candidate, and it could not be for themselves. These actions eliminated most of the outside influence and were institutionalized through two papal bulls: Aeterni Patris Filius, 1621, which established regulations for the election, and Decet Romanum Pontificem, 1622, which provided the ceremonies involved (and is not to be confused with a papal bull with the same title by Pope Leo X, which excommunicated Martin Luther) .

Gifted by God, temperate in nature, just in decision-making, Pope Gregory guided his Church in a most turbulent era and put into place programs that still continue 400 years later. He died on July 8, 1623, at age 69.

D.D. EMMONS writes from Pennsylvania.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples

Today, the program Pope Gregory began some five centuries ago, the Congregation for the Propagation of Faith, is known as the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. The current Vatican congregation continues to salute the work of Pope Gregory: “The task of the congregation has always been the transmission and dissemination of the faith throughout the whole world. It was given the specific responsibility of coordinating and guiding all the Church’s diverse missionary efforts and initiatives. These include: the promotion and the information for the clergy and of local hierarchies, encouraging new missionary institutes and providing material assistance for the missionary activity of the Church. Thus the newly established congregation became the ordinary and exclusive instrument of the Holy Father and of the Holy See in its exercise of jurisdiction over all the Church’s missions and over missionary cooperation.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..