Better Call Paul

The making of missionary disciples

Edward P. Hahnenberg Comments Off on Better Call Paul

No collaborator is more important to today’s pastor than the lay ecclesial minister. It’s difficult to imagine even a small parish without one or two lay ministers on the staff working alongside the pastor, helping to coordinate everything from baptismal preparation to Communion for the homebound. Larger parishes employ ministerial teams composed of lay pastoral associates, catechetical leaders, directors of faith formation, music directors, outreach coordinators, youth ministers and more. They have become a familiar part of the Catholic parish — as natural as pews in the church or announcements after Mass. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, 44,556 lay ecclesial ministers currently serve in U.S. parishes — a number that has more than doubled since they first started collecting data in 1990.

Almost 20 years ago, the U.S. bishops looked out on this burgeoning ministerial reality and concluded, “Lay ecclesial ministry has emerged and taken shape in our country through the working of the Holy Spirit.” It seems, the bishops suggest, that these “co-workers in the vineyard” are truly a gift from God.

More recently, Pope Francis has drawn renewed attention to lay ministry with his effort to revive a post-conciliar initiative of Pope Paul VI. By establishing the officially instituted lay ministry of catechist, Pope Francis affirmed a ministry that has been historically significant and remains vitally important in Catholic communities around the world.

As U.S. bishops discern how to implement the pope’s vision in the United States, we should not lose sight of two things. First, the ministry of catechist is just one of many important lay ecclesial ministries within the Church. (Pope Francis has in mind the role of catechist as it evolved in mission territories. Thus in the U.S. context the instituted ministry applies more to the parish “catechetical leader” than the volunteer catechist.) Second, this lay ministry — like all ministry, including the ordained — must always be seen within Pope Francis’ larger dream of a “missionary option” for the Church, one in which a missionary impulse transforms everything, “so that the Church’s customs, ways of doing things, times and schedules, language and structures can be suitably channeled for the evangelization of today’s world rather than for her self-preservation” (Evangelii Gaudium, No. 27).

For Pope Francis, the ultimate goal is not “ministers” preoccupied with preservation, but rather “missionary disciples” bound for areas beyond the walls of the Church. If that is the case, then we might look for inspiration not to past administrators but to past missionaries. We might call on that first great missionary, the apostle Paul, for insight into how pastors and lay ecclesial ministers today can work together to serve a Church that is everywhere and always on a mission.

Paul’s Example

St. Paul may seem like a strange choice for reimagining ministry today. After all, Paul was not a pastor. Nor is he an ideal model for the role. Raymond E. Brown once pointed out that there is a big difference between the Paul we meet in the authentic Pauline letters and the Paul we meet in the so-called pastoral letters of the New Testament. In Galatians, Philippians and 1 Corinthians, we meet a fiery and dynamic missionary, someone always on the go and not afraid of offending anyone. In the pastoral epistles of 1 and 2 Timothy, we find a different image of the ideal minister: one who is measured, diplomatic, respectable and stable.

So different are these two images that one wonders if Paul himself would have been able to meet the qualifications for a bishop laid out in 1 Timothy! It is difficult to describe as “dignified” (cf. 1 Tm 3:2) the guy who wished that his circumcising adversaries would slip with the knife and castrate themselves (cf. Gal 5:12). This was clearly not Paul’s most pastoral moment.

Paul was an amazing missionary, but he would have made a lousy pastor. As Brown concludes, it was probably best for everyone that Paul’s missionary genius kept him on the move.

Another reason Paul may seem like an odd choice is the romanticized image of the apostle that many of us carry around in our heads. We tend to think of Paul as a lone ranger, a solitary genius, the only one courageous enough to stand up to Peter, the heroic missionary single-handedly carrying the Gospel to the gentiles.

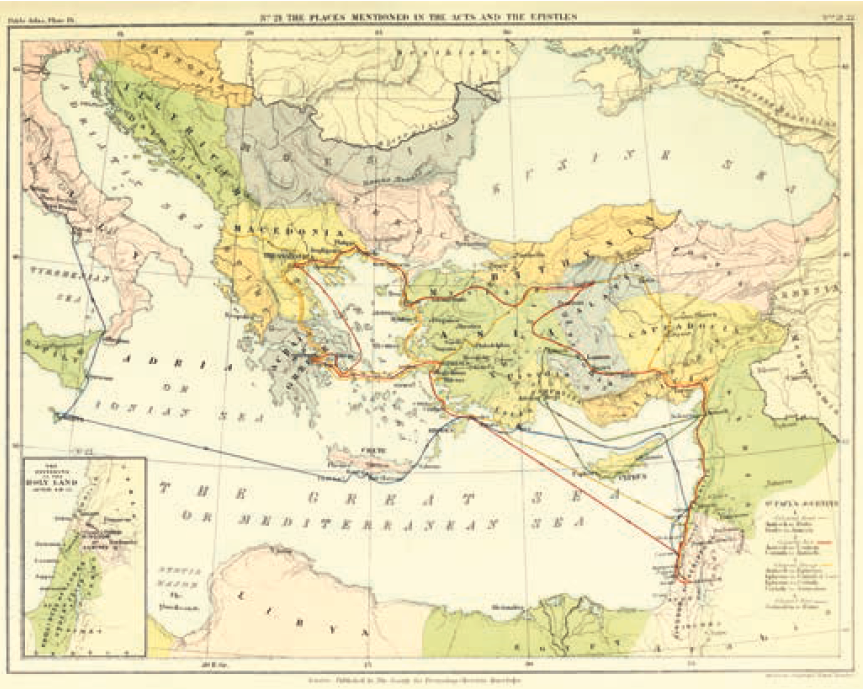

This is a false portrait, an idealized image. Recent scholarship has made abundantly clear how much Paul depended on others — men and women whom he called fellow apostles, ministers, partners and, most commonly, co-workers in Christ. If we take Acts of the Apostles and the whole Pauline corpus, we find as many as 95 different individual co-workers named. If we limit ourselves to the authentic Pauline letters, we learn of 36 significant men and women who were crucial to the success of Paul’s ministry. These collaborators included Prisca and Aquila, Phoebe, Timothy, Titus, Luke, Barnabas, Apollos, Andronicus, Junia, Tryphaena, Tryphosa and many others.

Paul literally survived because of the help and hospitality of fellow Christians. But these co-workers were not just hosts. They were active collaborators. They traveled with him, ministered with him, helped him compose letters. They “risked their necks” with him, as Romans 16:4 says of Prisca and Aquila, a married couple that played a key role in the evangelization of Corinth, Ephesus and Rome.

It is worth reflecting for a moment on this dynamic duo. Indeed, in their document Co-Workers in the Vineyard of the Lord, the U.S. bishops lift up these “lay” collaborators as inspiration for the work of lay ecclesial ministers today: “The same God who called Prisca and Aquila to work with Paul in the first century calls thousands of men and women to minister in our Church in this twenty-first century. This call is a cause for rejoicing.”

Prisca (Priscilla in Acts) and her husband, Aquila, appear six times in the New Testament (cf. 1 Cor 16:19; Rom 16:3; Acts 18:1-3, 18, 26; 2 Tm 4:19). The two are always named together, and usually with the woman’s name first, which would have been unusual and may suggest her greater prominence in the community. Prisca and Aquila were tentmakers like Paul. They welcomed him to Corinth when he came there around A.D. 50, providing him with a job and shelter (Acts 18:1-3). There they lived, worked and preached together for 18 months. The couple then left behind their business and friends and moved with Paul to Ephesus, where Paul left them in charge of the church as he moved on to Antioch and Galatia (vv. 18-21). In Ephesus, the two attended synagogue, preached the Gospel, taught the Faith to Apollos, among others, and hosted Christian gatherings in their home (vv. 24-26).

The author of Acts explains that Priscilla and Aquila had first come to Corinth shortly before Paul arrived there, as a result of Emperor Claudius expelling “Judeans” from Rome (cf. Acts 18:2). All the evidence suggests that the two were followers of Jesus before they met Paul, which is probably why they gave him refuge in the first place. Indeed, they were leaders in the Church — original and creative evangelists who led Christian gatherings in Rome and continued that practice in Corinth, and later in Ephesus. Sometime in the mid-50s, they returned to Rome from Ephesus, apparently as an advance team for Paul. In his Letter to the Romans (c. A.D. 57), Paul greets them first, calling them “my co-workers in Christ Jesus, who risked their necks for my life, to whom not only I am grateful but also all the churches of the Gentiles; greet also the church at their house” (16:3-5).

Making of Missionary Disciples

In a certain sense, the development of lay ecclesial ministry over the past 50 years is a new thing. Catholic parishes before the Second Vatican Council did not have theologically educated, professionally prepared, vocationally committed laywomen and laymen working full-time in important roles of ministerial leadership. No one had ever heard of a director of religious education, a parish social justice coordinator or a youth minister who was not a priest. In that sense, the rise of lay ecclesial ministry represents a paradigm shift for the life of the Church. It may even prove to be among the most lasting ministerial transformations in the Church’s history — on a par with the changes to the Church brought on by the rise of communal forms of monasticism in the fifth century, the birth of mendicant orders in the 13th century or the explosion of women’s religious communities in the 19th century.

In another sense, however, lay ecclesial ministry is not new. The kind of collaboration called for among today’s co-workers goes back to the earliest written records we have of the Jesus movement, the letters of St. Paul. It is significant that Pope Francis begins his apostolic letter Antiquum Ministerium, in which he establishes the instituted lay ministry of catechist, not with contemporary needs or modern expectations but with the Bible. He calls on Paul to remind us that ministerial diversity and the demand for collaboration go back to the very beginning. It is the tradition that “encourages the Church in our day to appreciate possible new ways for her to remain faithful to the word of the Lord so that his Gospel can be preached to every creature” (No. 2).

To become a missionary Church will require a Pauline boldness to recruit and equip co-workers for the vineyard of the Lord. Are we praying for vocations to lay ecclesial ministry with the same fervor that we pray for vocations to the priesthood and religious life? Are we inviting young people to use their gifts through full-time ministry? Are we paying lay ministers on our staff a just wage? Are we mentoring them or supporting their further education? Are we investing resources in the formation of future lay ecclesial ministers at the same level we invest in the formation of seminarians and candidates for the diaconate? Are we directing parishioners in need to the lay minister on staff best able to respond, thus validating their competence, authority and gifts as a minister?

Looking out on a world that did not know Jesus, the apostle Paul knew that he could not carry the good news alone. “Today, too,” Pope Francis writes, “the Spirit is calling men and women to set out and encounter all those who are waiting to discover the beauty, goodness, and truth of the Christian faith” (Antiquum Ministerium, No. 5). Every one of the baptized is called to become a “missionary disciple.”

But the pope continues: “It is the task of pastors to support them in this process and to enrich the life of the Christian community through the recognition of lay ministries” (No. 5). Essential to the making of missionary disciples are those lay ecclesial ministers who serve alongside the ordained, “like those men and women who helped the apostle Paul in the Gospel, working hard in the Lord” (No. 6).

EDWARD P. HAHNENBERG, Ph.D., holds the Breen Chair in Catholic Theology at John Carroll University in Cleveland. He served as theological consultant to the USCCB Subcommittee on Lay Ministry in its preparation of the document Co-Workers in the Vineyard of the Lord: A Resource for Guiding the Development of Lay Ecclesial Ministry.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Laity’s Important Role

The U.S. bishops’ document Co-Workers in the Vineyard of the Lord states: “Today in parishes, schools, Church institutions, and diocesan agencies, laity serve in various ‘ministries, offices and roles’ that do not require sacramental ordination but rather ‘find their foundation in the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation, indeed, for a good many of them, in the Sacrament of Matrimony.’ What Pope Paul VI said of the laity thirty years ago — and what the Catechism of the Catholic Church specifically repeats — has now become an important, welcomed reality throughout our dioceses: ‘The laity can also feel called, or in fact be called, to cooperate with their pastors in the service of the ecclesial community, for the sake of its growth and life. This can be done through the exercise of different kinds of ministries according to the grace and charisms which the Lord has been pleased to bestow on them.’ In parishes especially, but also in other Church institutions and communities, lay women and men generously and extensively ‘cooperate with their pastors in the service of the ecclesial community.’ This is a sign of the Holy Spirit’s movement in the lives of our sisters and brothers. We are very grateful for all who undertake various roles in Church ministry. Many do so on a limited and voluntary basis: for example, extraordinary ministers of holy Communion, readers, cantors and choir members, catechists, pastoral council members, visitors to the sick and needy, and those who serve in programs such as sacramental preparation, youth ministry, including ministry with people with disabilities, and charity and justice’” (p. 9).

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..