Pope Francis on Faith and Reason in a Skeptical Age

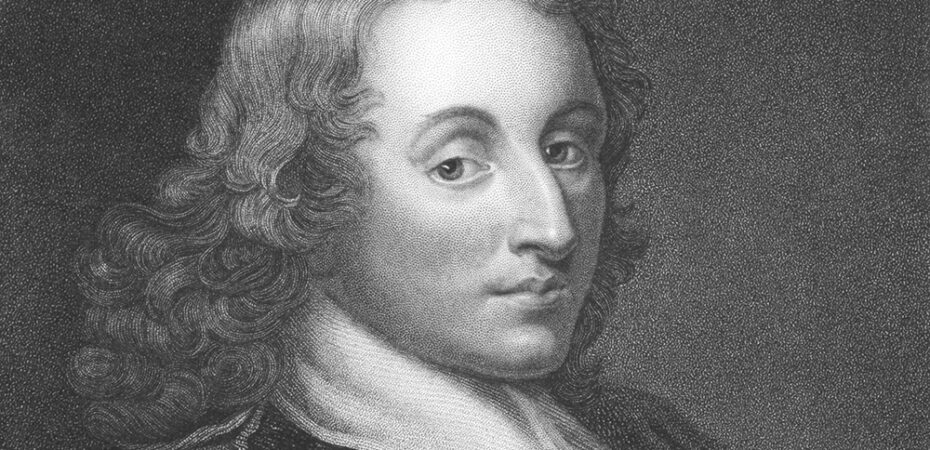

Five aspects to ponder concerning Blaise Pascal’s importance

Father Ronald D. Witherup Comments Off on Pope Francis on Faith and Reason in a Skeptical Age

More than 10 years on, Pope Francis continues to surprise. One such occasion occurred in the early summer of 2023 when he published an apostolic letter that seemingly flew under the radar. On June 19, the pope promulgated Sublimitas et Miseria Hominis (“The Grandeur and Misery of Man”) for the 400th anniversary of the birth of the famous French mathematician, inventor, philosopher and Catholic writer Blaise Pascal. Why this 6,000-word letter deserves more attention is worth pondering, especially for priests.

We must first recall some of the facts of this well-known French figure who is usually considered one of the most refined Catholic writers of all time. Born June 19, 1623, in Clermont-Ferrand, in the magnificent Auvergne region of central France, Pascal was a child prodigy. Despite frequent bouts of ill health, he vigorously pursued broad intellectual interests encompassing physics, mathematics, geometry, philosophy and, ultimately, Catholic beliefs.

While his important scientific inventions are too numerous to mention here, he is most renowned for his book “Pensées” (“Thoughts”), a collection of reflections published posthumously in 1670. The book is generally considered the most elegant set of essays in the French language.

Although Pope Francis overtly focuses on this book, which is a profound defense of the Catholic faith that began after Pascal’s dramatic conversion experience in 1654, he does not gloss over Pascal’s multiple contributions to the scientific growth of humanity. In fact, it is the intersection of Pascal’s faith perspective and his exceptional capability in human reasoning that motivated the pope’s reflections. I will summarize five main aspects of Pascal’s importance based on the Holy Father’s apostolic letter.

Faith and Reason

Perhaps the most important observation concerns the relationship between faith and reason. This is a perennial topic in Catholicism. The famous dictum fides quaerens intellectum (“faith seeking understanding”) expresses that there is an innate relationship between human reason and faith, which transcends rational thought. Rooted in the teachings of St. Augustine, the phrase was made famous by Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) in the early Middle Ages.

Pope St. John Paul II published an important 1998 encyclical, Fides et Ratio (“Faith and Reason”), on this theme. It explains the complex relationship between faith and human reason, but it mentions Pascal only twice, in connection with the latter’s philosophical inquiry. By comparison, Francis’ entire letter is on Pascal’s thought, and it shows the profound connection between these two essential aspects of human existence.

Francis acknowledges explicitly “Pascal’s brilliant and inquisitive mind,” which did not recede into the background after Pascal’s almost mystical experience of conversion on Nov. 23, 1654. Usually called the “night of fire,” Pascal’s intensely personal conversion to the Catholic faith marked the rest of his life, to his death in 1662. It produced in Pascal a deep love for the person of Jesus Christ. It also led to a more ascetic life, in which he increasingly devoted himself to the poor and a life of charity.

For priests, Francis’ invitation is to make Pascal our “traveling companion, accompanying our quest for true happiness and, through the gift of faith, our humble and joyful recognition of the crucified and risen Lord.” What I find so important in this invitation is its implicit acknowledgment that human reason is not the enemy of faith. Using our intellect, as Pascal did, to deepen our understanding of how God is at work in the universe remains a challenge. We live in an age that either increasingly over-exalts human achievement or disdains human ingenuity and remains skeptical of science. As a scientist, inventor and philosopher, Pascal never stopped his scientific inquiry, even after his conversion. In fact, Francis points out that his newfound faith spurred him to reflect on the very human challenges of his age.

The Human Condition

A second aspect of Pascal’s thought is his incessant reflection on the human condition. Francis asserts that Pascal always pondered the question posed by Psalm 8:5: “What is man that you are mindful of him, / the son of man that you care for him?” He quotes Pascal’s brilliant response: “What is man in nature? … Nothing with respect to the infinite, yet everything with respect to nothing.” Here we see Pascal’s appreciation of the paradoxical situation of humanity.

Pascal used his ingenuity to try to improve the quality of people’s lives. Francis points, for example, to his invention in Paris of “five-penny coaches,” the first public transportation system, which enabled Parisians to travel inexpensively throughout the city. His scientific and mathematical inventions also remain seminal. He designed an arithmetical machine that is considered a precursor of the modern computer. His contributions to geometry and physics are considered equally significant because they confirmed and elaborated on insights from ancient inventors like Euclid.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Our Human Condition

“If Blaise Pascal can attract everyone, it is above all because he spoke so convincingly of our human condition. Yet it would be mistaken to see in him merely an insightful observer of human behavior. His monumental Pensées, some of whose individual aphorisms remain famous, cannot really be understood unless we realize that Jesus Christ and sacred Scripture are both their center and the key to their understanding.”

— Sublimitas et Miseria Hominis, sixth paragraph

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

If much of Pascal’s contribution was for the betterment of human existence, he also perceived the plight of so much of humanity which was impoverished, unhappy and imprisoned by a certain helplessness. Francis quotes Pascal’s insightful perception of the contradictory nature of the human condition. “What a fantastic creature is man, a novelty, a monstrosity, chaotic, contradictory, prodigious, judge of all things, feeble earthworm, bearer of truth, mire of uncertainty and error, glory and refuse of the universe! Who can undo this tangle?”

Pascal’s ultimate response to this contradictory state of human affairs is found in his appreciation of Scripture and the Church’s tradition. The details of this response grew out of an almost indescribable experience of the risen Lord, which became the basis for his later life.

Role of Mysticism

It may strike us in our day as curious that such a brilliant genius should be susceptible to ethereal experiences, which can only be described as “mystical.” But, as is well known, grace works through nature in its own mysterious ways. Pascal himself describes his intensely personal encounter with God using the image of “fire.” He associated it with the biblical description of Moses’ mysterious encounter with God in the burning bush (cf. Ex 3:1-6). He also spoke of the simultaneous experience of “tears of joy.” It was an overwhelming encounter with God, and ultimately with his Son, Jesus Christ, who for Pascal became the center of existence.

The Pope admits that we can never know exactly what Pascal experienced that night. What is clear is the total transformation that came upon him and gave him a new direction in life. It was an experience of the love of God that led him to a life of charity. It was a true conversion, a change of heart, mind, soul and his entire being. It ultimately led to his deep reflections (pensées) on the truth of the Catholic faith.

Truth

Yet another significance of Pascal’s thought is his utter commitment to pursuing the truth. The use of his outsized human intellect, as well as his refined perceptions of faith, Scripture and Catholic tradition, led him to the conviction that the pursuit of truth was essential to human existence. Francis calls him “a tireless seeker of truth, a ‘restless’ spirit, open to ever new and greater horizons.” The pope also affirms that “Pascal’s confidence in the use of natural reason” unites him “to all seekers of truth” throughout history.

The Catholic faith has always insisted that there is such a thing as objective truth. She has also consistently condemned lying as a sin (cf. Catechism of the Catholic Church, Nos. 2482-85). Sadly, in our own age, influenced perhaps by the easy misuse of social media, we see the erosion of truth in almost every domain of human existence — business, politics, sports and even religion.

Promoting falsehood seems to be an epidemic. What counts is not truth but influence, self-aggrandizement and getting ahead. If anyone should be committed to preaching the truth, it should be us priests. Pascal warns against making truth itself an “idol, for truth apart from charity is not God.” Yet he never lessened his commitment to search for the truth as it could be perceived.

Charity and Love

A final point to emphasize from the teachings of Pascal concerns the primacy of charity. Charity is the love of God expressed in humanity. After his conversion, Pascal devoted himself to simplicity of life and outreach to the poor. Indeed, he desired to “die in the company of the poor” and apparently did so, dying “with the simplicity of a child.”

Francis, it should be noted, does not gloss over a certain background of Pascal’s life that might cause some to back away from him. Pascal became involved in the Jansenist controversy of the 17th century that embroiled the Church of that era. Although he was not formally a member of this eventually heretical movement associated with Port-Royal, outside Paris, he did undertake their defense through a series of writings known as “The Provincial Letters” (1656-57).

The danger, of course, was a kind of neo-Pelagianism, the age-old heresy, which overemphasized human effort toward perfection and neglected, or even denied, the role of grace. In any case, Francis acknowledges this blemish on Pascal’s ecclesial record but also credits him “with candor and sincerity of his intentions.”

Ongoing Relevance

These five main points do justice neither to the apostolic letter of Pope Francis nor to Pascal’s legacy. They are, however, an open invitation to draw on our Catholic tradition through the mind of a distant figure to extract from our storehouse of wisdom both old and new (cf. Mt 13:52), which can serve us and future generations.

As a lay Christian, Pascal used all his God-given talent in his short 39 years of life to improve the human condition, both materially, through his inventions and intellect, and spiritually, through his profound writings. To be honest, I had not actually read Pascal’s “Pensées” for many years. So, reading Francis’ apostolic letter was like rediscovering a long-forgotten gem tucked away in a dark closet. Perhaps we moderns prefer to search for glittering trinkets and sparkling new ideas. But the reality is, not all that glitters is gold. In the figure of Pascal, Pope Francis has reminded us that what should be cherished are eternal truths, not passing fancies. Pascal focused on the former.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Seeking Truth — A Never-Ending Task

“I would suggest that everyone who wishes to persevere in seeking truth — a never-ending task in this life — should listen to Blaise Pascal, a man of prodigious intelligence who insisted that apart from the aspiration to love, no truth is worthwhile. ‘We make truth itself an idol, for truth apart from charity is not God, but his image; it is an idol which must in no way be loved or worshipped.’”

— Sublimitas et Miseria Hominis, paragraph 7, from Pensées

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

We priests have a particular opportunity to enlighten our congregations about this overlooked figure in the Catholic tradition. I do not advocate preaching about Pascal, as such, though it would not hurt to draw attention to this apostolic letter. Rather, reading Francis’ letter may well spur one to apply insights from this fascinating figure to one or another scriptural lesson that may come up in the liturgical cycle. If this helps us rekindle our efficacy in promoting truth in a skeptical age, then so much the better.

SULPICIAN FATHER RONALD WITHERUP is former superior general of the Society of Saint Sulpice and author of many books on biblical and theological themes.