The Penitential Psalms

Seven voices crying out

Father Harry Hagan Comments Off on The Penitential Psalms

Jesus opens his ministry with a call to repentance: “This is the time of fulfillment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel” (Mk 1:15). Unlike John the Baptist, who called for repentance so that the Kingdom might come, Jesus calls people to repentance because the Kingdom has come among us and offers us the grace of forgiveness. This call builds on a sense of sin and the need to turn and return to God, already captured in the Old Testament, particularly in the psalms.

At least since Cassiodorus in the sixth century, the Church has recognized seven psalms as the classic expression of this repentance: Psalms 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130 and 143. Innocent III (r. 1198-1216) called on the Church to pray these psalms during the days of Lent, and Pius X (r. 190314) made them part of the Friday ferial office of Lent. The USCCB continues to recommend them as an expression of repentance, particularly during Lent.

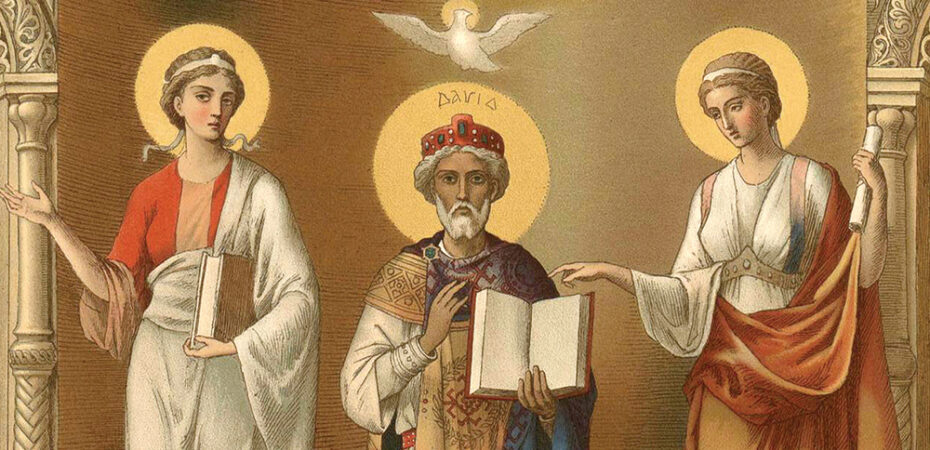

Though the tradition identifies David as the author of the Psalter, the book contains many voices. St. Augustine understands all the psalms as the prayer of Christ — either Christ the Head or Christ the Body — that is, the Church. For him, the Psalter becomes the prayer of the Totus Christus, the whole Christ. Still, the book gives us different voices, and I want to look at the individual voices of these seven psalms before joining them together.

Psalm 6:

‘Have pity on me, LORD, for I am weak.’

Psalm 6 is a good example of the many “prayer psalms,” in which a voice calls for God to come and act as the savior. Often called laments, they focus on the psalmist’s plight. In Psalm 6, though fearful of God’s anger, the voice cries out for mercy and healing. After pleas for rescue, we hear the lament:

“I am wearied with sighing; / all night long I drench my bed with tears; / I soak my couch with weeping. / My eyes are dimmed with sorrow, / worn out because of all my foes” (6:7-8).

The depth of personal anguish gives the lament the power to move not only God but all who hear the cry. Immediately after this, there is a shift. The psalmist orders the foes to back away, affirming that “the LORD has heard the sound of my weeping” (v. 9)

This psalm, like other laments, divides into two distinct moments. In the first, the voice cries out from the midst of great trouble, typically marked by fear and desolation. Abruptly, there follows an announcement of redemption.

Scholars have suggested that these psalms were used in a ritual, allowing a person to experience their anguish again, followed by an oracle of salvation announcing God’s intervention. The psalm’s second part responds with a thanksgiving hymn. Psalm 6 gives us these two moments: a prayer in the midst of the trouble followed by a declaration of salvation, bringing a sense of closure that allows us to rejoice with the psalmist.

Psalm 32:

‘Then I declared my sin to you’

Here, the sin lies in the past, and the voice begins by calling “blessed” those the Lord has forgiven. The psalmist then states a basic psychological reality:

“Because I kept silent, my bones wasted away; / I groaned all day long. / Then I declared my sin to you; / my guilt I did not hide” (32:3, 5).

The psalm celebrates the power of saying your sins out loud, the power of confession. Here, the voice addresses God directly:

“I said, ‘I confess my transgression to the LORD,’ / and you took away the guilt of my sin” (v. 5).

Priests know this from the experience of the confessional. By revealing what is hidden and shameful, a person opens the way to release and forgiveness. The voice then celebrates God as “my shelter” and calls others to be glad and exalt.

Psalm 38:

‘I am very near to falling.’

Some psalms have the raw emotion of country music, with the singer bluntly stating the problem and the pain. Here, the voice names God as the cause:

“Your arrows have sunk deep in me; / your hand has come down upon me” (38:3).

But the psalmist does not see God acting without cause: “There is no health in my bones because of my sin” (v. 4). Sickness is the punishment of God, and for this reason not just enemies but “friends and companions shun my disease” (v. 12). While sin may affect our health, the simple equation of sickness and sin is theologically problematic. Still, anyone who has visited the sick knows that they can feel unmoored guilt as they search for a reason to explain the inexplicable. Unlike Psalm 6, which ends with the assurance of recovery, the psalmist here senses the end is near and pleads:

“Do not forsake me, O LORD; / my God, be not far from me! / Come quickly to help me, / my Lord and my salvation!” (vv. 22-23).

By including this psalm, the Church stands with the sick who feel alone — abandoned by friend and neighbor, and even God.

Psalm 51:

‘Restore to me the gladness of your salvation’

By any measure, this psalm stands as a masterpiece in the Bible. The psalmist opens with a cry for mercy:

“Have mercy on me, God, in accord with your merciful love; / in your abundant compassion blot out my transgressions” (51:3).

The tone stands in contrast to the previous psalm. The voice is hopeful and trusting even as it admits “my transgressions.”

“For I know my transgressions; / my sin is always before me. / Against you, you alone have I sinned” (vv. 5-6).

Yet this repentant voice is not afraid to ask God for a new beginning:

“A clean heart create for me, God; / renew within me a steadfast spirit” (v. 12).

Like Isaiah 1, the voice rejects empty ritual and confidently asserts instead:

“My sacrifice, O God, is a contrite spirit; / a contrite, humbled heart, O God, you will not scorn” (v. 19).

This psalm may give pause to us priests who preside over the Church’s official liturgy. We understand that this is the personal offering and sharing of Christ himself. Still, rote repetition can drain the liturgy of life. The “contrite, humbled heart” must be nourished.

In the last two verses, we hear a new, second voice celebrating ritual sacrifice in Jerusalem. This voice comes from the time of the Babylonian exile and reflects an understated pathos that deeply feels the loss of Jerusalem’s liturgy. It longs for the restoration of its sacrifice. As human beings, we have a need to make concrete the unseen reality that we celebrate. The first voice seeks a true interior spirit, and the second values its outward expression. Together, the two voices capture this whole, which we, as priests, are called to celebrate for and with the People of God.

Psalm 102:

‘They perish, but you remain’

This psalm, like Psalms 38 and 51, ends without our knowing whether God acts for the psalmist. In Psalm 51, the voice is full of confident hope. In Psalm 38, the voice expresses an anguished heart yet, in the end, names the Lord as “my salvation.” This psalm mixes lament and praise with anguished resignation.

The opening section piles up heartfelt metaphors: days vanishing like smoke, a heart like grass, too wasted to eat, the psalmist like an owl in the desert, a lone bird on a rooftop, ashes for bread, tears for drink, days like a lengthening shadow. This river of metaphor creates the experience of being “lifted up” and “cast down.”

The middle section contains no reference to the psalmist. Rather, the voice begins with praise and then affirms: “You will again show mercy to Zion” (102:14). As at the end of Psalm 51, the psalmist speaks from the time of exile but with a hopeful voice. It predicts that “nations shall fear your name” (v. 16) and the Lord shall reappear in the rebuilt Zion. There, God will hear “the groaning of the prisoners” and will “release those doomed to die” (v. 21). Though unstated, this hope for Jerusalem becomes the foundation for the voice’s own hope in the last section.

Returning to the lament, the voice pleads that God “not take me in the midst of my days” (v. 25). This is not the plea of an old man, but the desperate plea of someone in midlife with a family half-raised, work half-realized, life half-explored. Abruptly, the voice shifts to creation, God’s handiwork, but all of it is changing and passing away, as is this voice. Only God remains without end. In the final verse, the voice looks only to future generations as the only hope for permanence, for “all wear out like a garment” (v. 27). Only God is without end.

Psalm 130:

‘Let Israel hope in the LORD’

Psalm 130 opens with one of the most famous lines in the Bible:

“Out of the depths I call to you, LORD; / Lord, hear my cry!” (Ps 130:1-2).

Down is almost always the place of depression and despair, and here the voice claims that place but begs for God to hear the cry. The next line evokes a fundamental human insight and invites the reader’s assent:

If you, LORD, keep account of sins, / Lord, who can stand? (v. 3).

The Grail Psalter underlines this insight with the translation “our sins.” Despite the depths from which this cry comes, the voice expects mercy and forgiveness. In Hebrew, the verbs “to hope” also mean “to wait” because waiting demands hope. Both look to the future, and the voice claims the image of the watchman in the night who both “waits” and “hopes” for the morning. It will surely come, as will the Lord’s mercy and redemption. Moreover, the voice expands this hope to Israel in the final line that affirms that God “will redeem Israel from all its sins” (v. 8). The personal has become a universal cry and hope.

Psalm 143:

‘For I am your servant’

Psalm 143 does not mention sin. Like Psalm 130, the voice acknowledges that “before you no one can be just” (143:2). Still, sin is not the issue. Some enemy “has pursued my soul / … has made me dwell in darkness” (v. 3). While this enemy could be a specific human being, the vagueness suggests not just a personal fight. It points us toward a more universal battle we must all frame for ourselves.

The psalmist expects to triumph, and the last line gives the reason: “for I am your servant.” The word “servant” belongs to the language of covenant, and the voice claims a covenantal relationship to a “lord” (ˀādôn) who also swears to protect the servant’s life. The assurance and intimacy of this relationship pervade the psalm. The first line highlights “faithfulness,” a basic virtue of covenant: “in your faithfulness listen to my pleading” (v. 1). The voice asserts its own faithfulness by asserting, “I remember … / the works of your hands” (v. 5). To remember is to keep the covenant.

The voice amplifies the intimacy with the language of the self: my spirit, heart and soul — my hands and my life. “Spirit” in Hebrew can also mean “breath, wind,” which here is faint and failing. The Hebrew “heart” not only feels but thinks, and here “despairs.” “Soul,” which translates the Greek psyche, refers to one’s whole self, one’s very being. Though the enemy has made the psalmist “dwell in darkness,” the voices hands over the self, whole and entire:

“I stretch out my hands toward you, / my soul to you like a parched land” (v. 6).

Covenant’s other primary virtue, ḥesed, is translated here as “mercy,” reflecting the Greek (cf. vv. 8, 12), but elsewhere it carries the meaning of steadfast and loyal love and expresses the fundamental emotion of covenant.

“In the morning let me hear of your mercy, [ḥesed] / for in you I trust” (v. 8).

As in Psalm 130, the morning becomes the image of salvation, and the voice has reason to hope in this merciful love — as it says: “for I am your servant” (v. 12).

The penitential psalms hold seven voices crying to God for mercy and forgiveness. They are different voices with different concerns and hopes. A group of seven often represents completion, but this group does not represent every possible voice. Still, this traditional group represents the Church’s voices, all whom the Church would embrace as the Body of Christ.

Joined with Christ the Head, they make up the prayer of the Totus Christus. Surely, it is right and just to join our voices to these seven psalms during Lent and ask forgiveness not only for my sins but also for the sins we commit against one another and the world.

FATHER HARRY HAGAN, OSB, is an associate professor of Scripture at Saint Meinrad Seminary in Saint Meinrad, Indiana.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Journal Your Way Through the Gospels and Psalms

Journaling Through the Gospels and Psalms , Catholic Edition (OSV, $34.95) offers readers to read, pray and journal their way through the Gospels and Psalms. The margins of this journal offer space to journal, take notes, record prayers, etc., while you dig deeply into the meaning of the passages and how they impact your life.

, Catholic Edition (OSV, $34.95) offers readers to read, pray and journal their way through the Gospels and Psalms. The margins of this journal offer space to journal, take notes, record prayers, etc., while you dig deeply into the meaning of the passages and how they impact your life.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….