Journeys Unveiled Through Journaling

Journal-keeping compliments other spiritual exercises

Susan Muto Comments Off on Journeys Unveiled Through Journaling

The art and discipline of journal-keeping serve as a compliment to other spiritual exercises like formative reading and meditative reflection. Priests have availed themselves of this practice to chronicle their journey of faith, the reasons for their hope and the motivating power of their love for the people of God entrusted to their care.

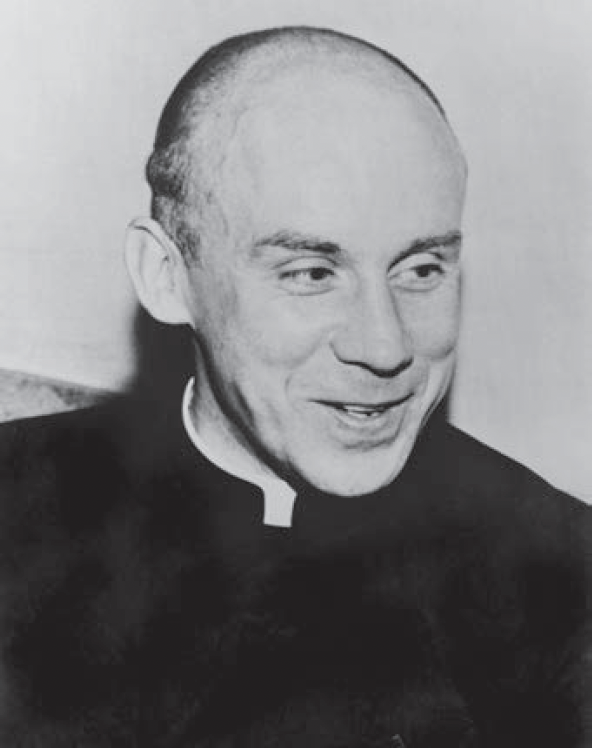

Classical examples of this practice include “Journal of a Soul: The Autobiography of Pope John XXIII” (Penguin-Random House, $17) and “The Sign of Jonas” (HarperOne, currently out of print but used copies available online) by Thomas Merton. Despite the abundance of obligations entrusted to them in ecclesial and monastic life, both priests slowed their pace long enough to keep, so to speak, an appointment with the Lord in their journal. There they revealed their responses to the inspirations of the Holy Spirit in and beyond the assignments required by their ministry.

An exemplary entry written by Pope St. John XXIII on Sunday, March 20, 1898, reads: “Humility, humility, still more humility! However, in all my distress I can still thank the Lord for not having abandoned me as I deserved. Thanks be to God, I still have the will to be good, and with this I must go on” (p. 20).

In a similar vein, Thomas Merton writes in an entry on June 13, 1947 (feast of the Sacred Heart): “Every creature that enters my life, every instant of my days, will be designed to wound me with the realization of the world’s insufficiency, until I become so detached that I will be able to find God alone in everything. Only then will all things bring me joy” (p. 51). An entry like this brought to the forefront of Merton’s attention why he had no choice but to rediscover the timeless truth that resting in the peace of Jesus had to permeate every activity he undertook.

Balanced Approach

Keeping a spiritual journal facilitates a balanced approach to prayer and participation. It encourages priests to take time to be present to the deeper meaning of everyday events. Recording what happens increases their awareness of the pressures associated with a performance mentality, so fixated on planning outcomes and fulfilling agendas that they risk losing touch with God’s will in the here and now.

Instead of allowing life to go by in a blur, journaling reveals its providential pattern in moments that might otherwise be forgotten in the sleepy stream of passing time. Recapturing this sense of wholeness and holiness is one of the best gifts of journal-keeping. Putting thoughts on paper lets priests delve into the directives they receive daily from the Holy Spirit. This practice sensitizes them to times when they are more tense than relaxed, more negative than positive, more resistant to God’s grace than receptive to it.

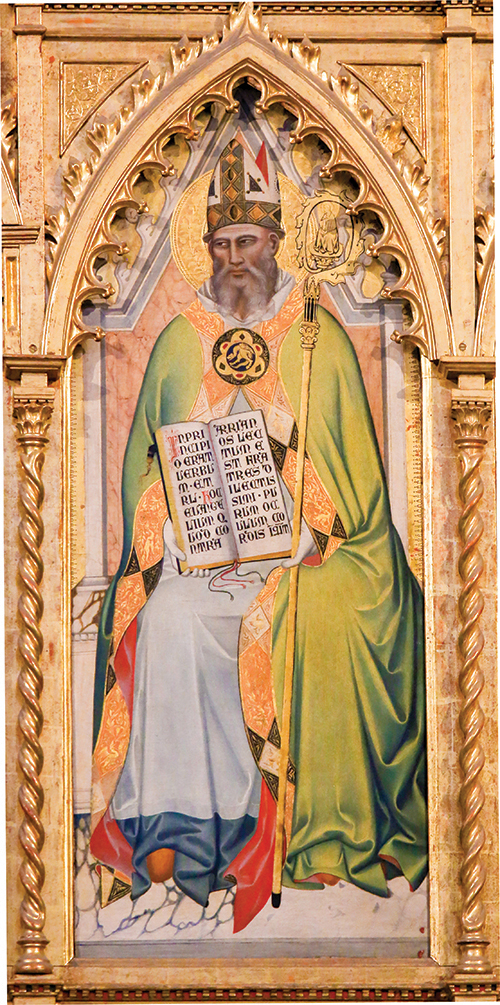

At the beginning of Book 9, Chapter 1 of “Confessions,” St. Augustine of Hippo, a new Catholic at the time, writes in his journal of the journey: “O Lord, I am your servant; I am your servant and the son of your handmaid. You have broken my bonds: I will sacrifice to you the sacrifice of praise. Grant that my heart and my tongue may praise you. Grant that all of my bones may say, ‘Lord, who is like unto you?’”

The Source and Center

Reading such timely, yet timeless, testimonials confirms the desire deep in every priest’s heart to let the Lord be the source and center of their life. Journaling is a way to focus on the mystery of God’s guiding will amid the demands and duress of the day. Writing is a way to reaffirm commitment to record the presence of the Lord in the here and now. Journaling gathers otherwise scattered thoughts into a more refined appraisal of a life of love and service to the People of God.

Prayers like these echo their most heartfelt concerns:

• Lord, help me to disclose with candor and courage what you are asking of me.

• Let this act of writing help me to haul to the surface thoughts I don’t even know are there.

• Let journaling be a window through which to see pitfalls on the road and rocky places of which I might not otherwise be aware.

• Let me reread the jottings I have written to see what I have learned today while remembering the flaws of the past and rekindling my hopes for the future.

The more the demands of ministry proliferate, the more priests need to consider the practice of journaling as a way to integrate contemplation, likened to Mary sitting at the feet of Jesus, and action, resembling Martha doing her daily tasks. This blessed bridge between spirituality and functionality characterizes the whole of their vocation and comes to the fore, especially during celebration of the Eucharist. There, above all, they realize that thanksgiving to God and obedience to God’s will must be the ground of their apostolic and ministerial outreach. To be avoided at all costs is mere activism that causes service to degenerate into a merely functional enterprise, placing priests at risk of ministerial burnout and leading, in the worst cases, to a vocational crisis.

Renewal of Commitment

On his retreat from Nov. 27 to Dec. 2, 1926, Pope St. John XXIII wrote in his journal: “The time I give to active work must be in proportion to what I give to the work of God, that is to prayer. I need more fervent and continual prayer to give character to my life … the company of Jesus will be my light, my comfort, and my joy” (“Journal of a Soul,” p. 208).

This Christ-conscious mode of presence led Merton to a renewal of his priestly commitment to defend the faith at all costs. This intention seems to have gripped him when he wrote on April 6, 1950: “The task of a priest is to spiritualize the world. He raises his consecrated hands and the grace of Christ’s resurrection goes out from him to enlighten the souls of the elect and of them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death. Through his blessing material creation is raised up and sanctified and dedicated to the glory of God. The priest prepares for the coming of Christ by shedding upon the whole world the invisible light that enlightens every [person] that comes into the world. Through the priest, the glory of Christ seeps out into creation until all things are saturated in prayer” (“The Sign of Jonas,” p. 301).

By recording in their journal events that bolster their vocational life, priests can dig below surface happenings to disclose the deeper meaning of their calling in the Lord. This helps resist the temptation to become so caught in the busyness of ministry that they neglect the time it takes to embellish their encounters with God. Journaling helps guard against excessive introspection and keep the commitment to being a companion of Christ as the centerpiece of their concern.

Like a conversation with a trusted friend or spiritual director, journaling can be a step toward replacing self-scrutiny and negative thinking with the virtues of self-forgiveness and appreciative living. As Merton wrote on March 3, 1950: “The Christian life — and especially the contemplative life — is a continual discovery of Christ in new and unexpected places. And these discoveries are sometimes most profitable when you find him in something you had tended to overlook and even despise. Then the awakening is purer and its effect more keen, because he was so close at hand, and you neglected him” (p 282).

Emerging Insights

The more journaling becomes a regular practice, the more new insights may begin to emerge. Rather than circling aimlessly around a certain point, a pattern of purpose may present itself. Their journal can attest to the fact that they are on the right path, helping to reveal the direction in which God wants them to go. The journal may evidence that they have come to a deeper recognition of God’s call from the time of their initial discernment of their vocation to the present moment.

Writing, so to speak, slows down the flow of time and lets priests gain insight into what happened in this apostolic activity or that pause for prayer. Facing their limits and talents encourages priests, the older they grow, to live by these prophetic words: “Although our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day” (2 Cor 4:16).

Kept regularly over several years, journaling can provide priests with a realistic perspective on the divine design of their life. Rereading their journal offers ample evidence that times of joy and suffering have become sources of hope, confirming their place in God’s plan.

Recall Augustine’s “Confessions” in this light. His meeting with St. Ambrose and his encounter with the Scripture text read in the garden, following a long period of doubt and debate with God, were threads that suddenly revealed a providential pattern. He saw, as if for the first time, the meaning of his life to Christ and the Church. He beheld the guiding hand of God in the events leading up to and following his conversion.

“Confessions” became an occasion for spiraling down and reflecting on significant experiences of doubt and trust, the ramifications of which could not be grasped unless he wrote about them. In his now famous meditations in Chapter 27 of Book 10, he wrote: “Too late have I loved you, O Beauty, so ancient and so new, too late have I loved you! Behold, you were within me, while I was outside. … You were with me, but I was not with you.”

It is hard to predict in what direction writing will take priests because there is a kind of self-generating power to written words. One phrase, one sentence, one paragraph may lead to another. Their pen may flow over the page, or they may struggle for each word. How rested or how pressured they feel affects this practice.

It may also happen that what they write moves from description into dialogue with God. Their journal entry becomes like a letter to Jesus. Suddenly a word well-read will spark a thought that prompts them to turn to their journal and transcribe what they are feeling.

Leading to Knowledge

The act of writing shapes the blur of ideas, notions and hunches, leading to more knowledge of self, others and God. Journaling keeps them from pulling one point out of the whole perspective of life. By keeping a journal they have an opportunity to return to this or that insight and reflect on it again.

Their journal also provides an opportunity for growth in gratitude and humility. They feel grateful that the Lord has graced them with new insights into whatever has kept them from being more closely united to him. They feel humbled at the thought of his love and care, encouraging them to live a more Christ-centered life and to find the right balance between limits and blessings, character flaws, and fresh openings for silence, solitude and prayer.

In the journal he kept on the psalter, St. Charles de Foucauld wrote in his meditations on Psalm 32: “Eleven years ago, at this time, you converted me. Eleven years ago, without my seeking you, you brought my sinful soul back into the sheepfold. For eleven years have my sins been forgiven. … How good you were! Divinely good, good not only in the infinite benefit … of my conversion, but by the thousand tactful acts and the divine caresses with which you surrounded it!” (“St. Charles de Foucauld Meditates on the Psalms: The Tool Shed in Nazareth,” pp. 201-2).

Far from being a forced discipline, journal-keeping fosters communion with the living God. It lets priests feel the gentle touch of the Lord; it reawakens their yes to God, freely given, and reinforces the sharing of other-centered love. They realize day after day that God is greater than any one of his friends and servants could have imagined. Journaling has become an excellent way to direct each thought, each effort of life, to the vision of God and the peace promised through Jesus Christ, now and for ages to come.

SUSAN MUTO, Ph.D., is dean of the Epiphany Academy of Formative Spirituality in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and author of “Enter the Narrow Gate: Saint Benedict’s Steps to Christian Maturity” (OSV, $15.95).

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Read more from these references

– St. Augustine, “The Confessions of St. Augustine,” translated by John K. Ryan (Image Classics, $18)

– Charles de Foucauld, “St. Charles de Foucauld Meditates on the Psalms: The Tool Shed in Nazareth,” edited by Rev. Leonard J. Tighe, translated by Katherine Fairbanks (Caritas Publishing, $12.45)

– Thomas Merton, “The Sign of Jonas” (HarperOne, currently out of print but used copies available online)

– Susan Muto, “Pathways of Spiritual Living” (Epiphany Books)

– Pope St. John XXIII, “Journal of a Soul: The Autobiography of Pope John XXIII” (Image Books, $17)

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..