Cultural Illusions and Prayer

Breaking down meritocracy and individualism in our spiritual lives

Father Richard M. Gula Comments Off on Cultural Illusions and Prayer

Prayer opens us to the presence of God, allowing us to create and sustain a resilient intimacy with God — an intimacy that makes our relationship to God the most important one in our life. Sustaining and deepening that relationship is the core energy of the spiritual life.

“Pray from where you are” is good spiritual advice. Understanding where we are can shape how we pray and what we expect of our prayer. Usually, “where we are” refers to our emotional state. We pray out of disappointment and sadness, as well as out of a sense of fulfillment and joy. Where we are, however, can also refer to our cultural environment. Culture has a subtle, yet deep influence on our expectations of the God to whom we pray and of ourselves as the one praying. If we are going to approach God from where we are, then we need to have a realistic sense of the cultural illusions that infiltrate and influence our prayer. Two stand out: meritocracy and individualism.

Meritocracy

Social psychologists tell us that to find our place in the world we create structures that allow for predictable behaviors that give us a sense of control. Meritocracy does that. It affirms a strong notion of personal freedom and responsibility and maintains that what we accomplish is the product of our own effort and talent. It is rocket fuel for launching the American dream. We reward talent and cultivate hard work. If things are going well for us, hosannas can be shouted. We deserve it, for we made it happen. The fruits of our efforts are owed to us by right. If things are not going well, then we must have brought it on ourselves, since it can’t be the result of complex social structures or other people over whom we have no control. The seductive illusion is that we are self-sufficient and self-made, more in control of our lives than is the case. We do not need to depend on anything outside our control. The COVID pandemic is “Exhibit A” proving this illusion false.

Meritocracy has a strong hold on our spiritual imagination. It is deeply rooted in our psyches from our early religious formation in a theology of retribution. Fueled by the false belief that God works on the merit system, meritocracy gives the illusion that we will get from God what we deserve. Retribution compels God to treat us according to our merit. If we work hard and do what is right, we will get rewarded; if we slack off and transgress, we will be punished.

The tyranny of merit runs amok in the Book of Job. If bad things do not happen to good people, then why is Job, a righteous man, being made to suffer? His friends try to show him that his misfortunes are brought on by some transgression of his, for that is how the world works on the merit system. However, at the end of the book, God renounces this assumption. The moral of the story of Job is that faith in God means to stand in awe before the mystery of creation and the majesty of God. Divine providence is not a function of rewards and punishments based on what we deserve.

The question of merit reappears in Christian theology in the debates about salvation. Can we earn/merit salvation through good works or is salvation a matter of God’s free grace? On the Pelagian side, salvation is a matter of merit and depends on how well we live. Augustine, by contrast, insisted that life in God is received not achieved. Yet, over time, his theology of grace became obscured by the illusion that the practices of the Church (like prayer, sacraments and good works) could generate merit and win God’s favor. The Protestant Reformation was born as a corrective.

Dispositions for Prayer

We need to try to break through the meritocratic illusion and allow ourselves to enjoy an intimate relationship with a completely benevolent God. Under the illusion that we will get what we work for, we spend our lives as workaholics for God, hoping that our efforts will make us worthy to win God’s favor and save our souls. If we continue to believe that we get what we deserve, then we leave no room for God’s mercy, that attribute of God so highly prized by Pope Francis as expressing the meaning of God’s love, which has nothing to do with the merit system.

The more we fall for the illusion that we are self-sufficient and self-made, the harder it is to accept our dependence and to learn gratitude and humility — the fundamental dispositions of prayer.

Dependence. Our life is more gift than achievement. Though we may have worked hard, we really can’t say we have become who we are all on our own. We are in debt, way over our heads, to the people who have shaped us, the social structures that have surrounded us, and the opportunities we have had to give in service of the gifts we have received. As Reinhold Niebuhr, an American social ethicist, once said, “Nothing we do, no matter how virtuous, can be accomplished alone.” We are all building on foundations we did not lay. All of these immanent dependencies mediate our dependence on God, the ultimate gift giver. A prayer life that does not acknowledge dependence is fertile soil for yielding arrogance that humiliates.

Gratitude. We are grateful because of grace. But meritocracy banishes all sense of grace. The more we conceive ourselves as self-made, the less reason we have to be grateful. Gratitude helps us resist the inclination of meritocracy to put ourselves first, to secure our interests and well-being over those of others. It also fights the temptation to pull back and harden ourselves to the needs of others. Gratitude follows upon recognizing that everything comes to us as a gift; nothing is ours by right. When we begin with God seeing us worthy of love (graced), then gratitude becomes the basic motive governing the whole of our lives. It lies at the basis of charity. Not being grateful is an enormous spiritual failure, for it takes the bounty around us for granted or makes us feel entitled to it as a right. A prayer life not rooted in gratitude will, in the end, cause ministry to become manipulative and self-serving.

Humility. Simply put, humility is being down to earth about ourselves. As the earth creature (formed by the Creator taking humus, earth, and breathing life into it), we are limited and dependent. Humility does not come easily to anyone living under the illusion of meritocratic independence with absolute control. Humility checks our passion for control by enabling us to live with limits, to choose to play the hand we have been dealt, to take a lighter grasp on life, and to let go of what we cannot change. With humility, we are able to contribute what we can and then lean back when it is time to trust in the gracious work of God and in the gifts of others to do what we cannot. Prayer rooted in humility helps us to become aware of our need for grace.

Individualism

Individualism is an illusion hitched at the hip to meritocracy. It rides the wave of meritocratic pride of being self-sufficient and self-made. As the offspring of original sin, self-centeredness is our default setting. The selfie is the iconic image of this illusion. Our increasing use of technology is funding the selfishness of narcissism. We are swimming in the ocean of the “big-me” and, like the fish looking for this thing called the ocean, we don’t even notice that we are immersed in it. Whereas we once understood personal identity to be defined in large part by our relationships, now we are defined by our own thoughts and feelings.

The illusion of individualism fails to take seriously that we are social by nature and made to share. The social dimension of being human is drawn from being created in God’s image. The central symbol of God in the Christian faith is “God is love.” This biblical symbol has been elaborated in the doctrine of the Trinity as a community of persons radically equal to one another while absolutely mutual in self-giving and receiving.

We are and can be human only in and through relationships. This is the most basic law of our nature. We have a self insofar as we are related to others and most certainly to God. We will survive to the extent that cooperation and not domination or competition becomes our primary way of relating to one an oher. Yet, in our larger geopolitical world, we seem to be absorbed in a power game of “who’s on top.” Everyone and everything becomes objects to dominate, manipulate and control. We have moved away from social concerns with a sense of collective good and toward individual needs of self-interest. Yet, our personal and global survival depends on our capacity to relate by respecting our differences and interdependence.

Practice of Prayer

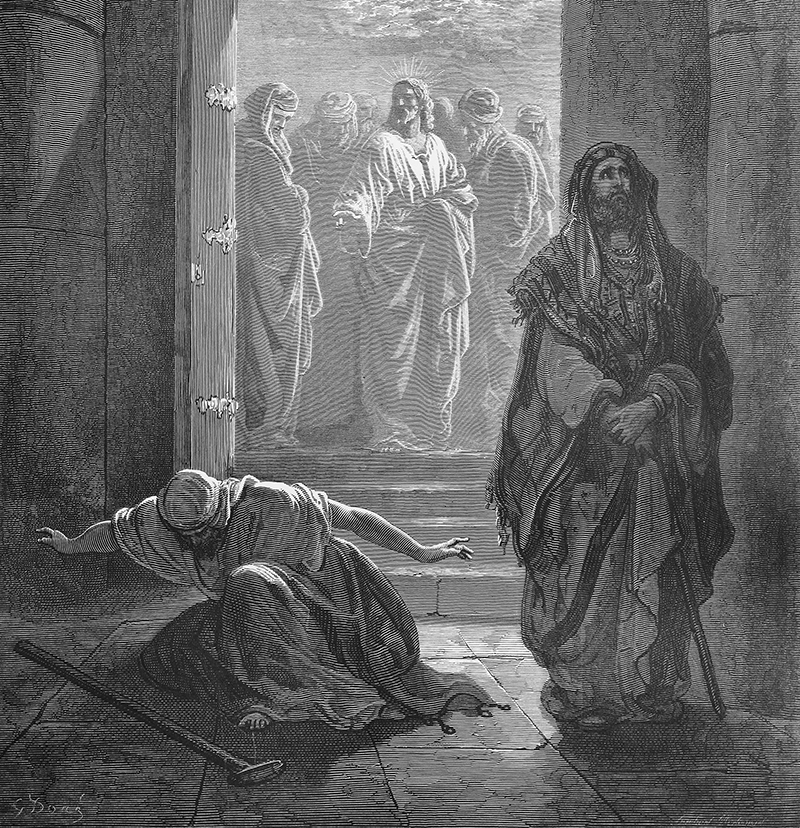

The practice of prayer in our lives creates the condition within ourselves that will make room for a kind of mystical union with God and all of creation. But to be allured by the illusion of individualism is to pray only for ourselves: “I need …” “I want …” “Help me.” Prayers like these reflect self-contained lives and inflate a superior self-image of privilege. But remember the parable of the Pharisee and the publican (cf. Lk 18:9-14). The Pharisee prays for himself and thanks God that he is not like other people. The publican, by contrast, declares himself in solidarity with all sinners and humbly recognizes his own need for mercy.

Without a rule of prayer that opens us to our interdependence, we risk becoming ego-driven. But with a prayer life that opens us beyond a private relationship with God to include communion with others, we create an opportunity to be free from our self-interest and more open to supporting the true interdependence that will enable everyone to thrive. Prayer that breaks through the illusion of individualism is prayer marked by solidarity.

Solidarity is the disposition that governs the ties that bind us together. Solidarity does not understand society as a loose association of individuals who stand side by side, bound together merely by self-interest. By contrast, it understands personal existence only in terms of the covenantal partnership of interdependence that binds us with others, the earth, and God. Solidarity stands in stark contrast to the cultural illusion of individualism that takes independence and separation as the norm. It constantly draws our attention to others to see them, not for how we can use them to serve our own interests and then discard them when they are no longer useful, but as partners with us, sharing our humanity. Solidarity reminds us that we are not the center of the universe. There are other centers of life, and we are to give proper weight to their claims upon us. In solidarity, we know that human life is a shared life, that cooperation is better than playing the Lone Ranger, and that give-and-take is better than grab-and-go. Solidarity forces us to recognize that, while there are some things that we want for ourselves, we might not pursue them right now so that the good of the whole might be better served.

Living in a world with these cultural illusions threatens to domesticate our life of prayer with egotistical desires. In the face of this challenge to relate to God as though we were entitled to all blessings as a right, we need to cultivate a healthy sense of dependence and nurture our life with the virtues of gratitude, humility and solidarity. With these, we can live in a deeper communion with God, others and creation.

FATHER RICHARD M. GULA, PSS, is a retired Sulpician priest who has served in provincial administration and in the education and formation of priests and candidates for ministry, lay and ordained.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Pope St. John Paul II on Solidarity and the Common Good

Speaking of solidarity as a key social justice principle, Pope St. John Paul said in the 1987 encyclical letter Sollicitudo Rei Socialis that solidarity is an authentic moral virtue, “not a feeling of vague compassion or shallow distress at the misfortunes of so many people, both near and far. On the contrary, it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all. … These attitudes and ‘structures of sin’ are only conquered — presupposing the help of divine grace — by a diametrically opposed attitude: a commitment to the good of one’s neighbor with the readiness, in the gospel sense, to ‘lose oneself’ for the sake of the other instead of exploiting him, and to ‘serve him’ instead of oppressing him for one’s own advantage” (No. 38).

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..