Staying in Sequence

When are we obliged to use these ancient hymns tucked before the Gospel?

Father Paul Turner Comments Off on Staying in Sequence

Who needs a sequence? After presiding over the Holy Week services that includes the blessing of palms, two proclamations of the Passion, the washing of feet, Eucharistic reservation, adoration of the cross, and the celebration of baptism and confirmation within a long and late Easter Vigil Mass, a priest awakens at the break of Easter dawn and takes a breath. Just a few more Masses and he can rest.

Surveying the Easter Sunday Liturgy of the Word, he notices something odd: a sequence. Who needs one of those?

A sequence is a hymn tucked into the Liturgy of the Word between the second reading and the Alleluia. It’s poetry. It interprets the meaning of the day’s historical celebration for the people who have gathered here and now.

How amazing, then, that the four sequences adorning the Lectionary for Mass all come from the Middle Ages. Three of the likely authors bridged the same century: Stephen Langton (d. 1228), Thomas Aquinas (d. 1274) and Jacopone da Todi (d. 1306). Wipo of Burgundy preceded them (d. 1048). Populists all, aware of the biblical and devotional foundations to the pertinent celebrations, they created something you might call “contemporary” to their day. And here we are, almost 1,000 years later, singing an old song unto the Lord.

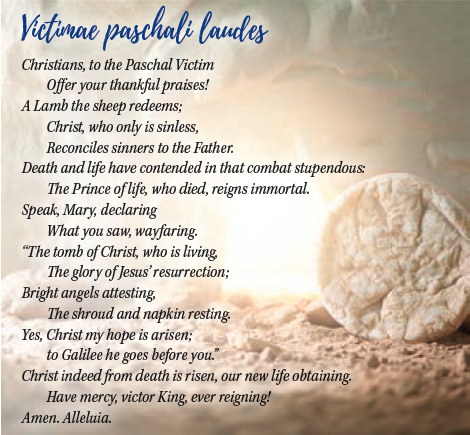

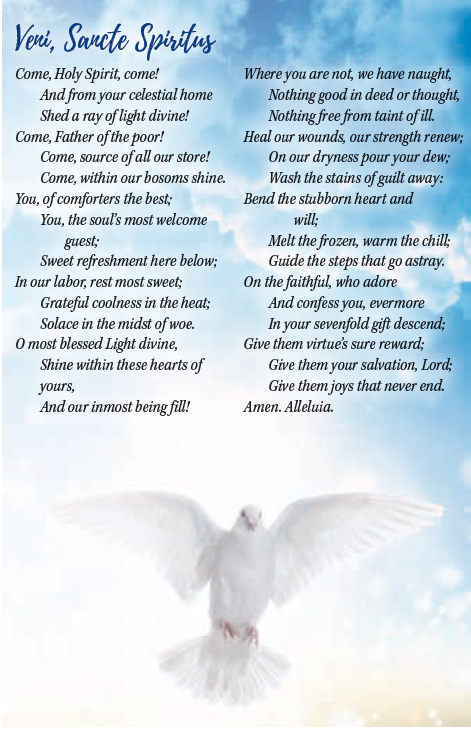

In reality, though, none of these sequences is addressed to the Lord. Langton’s Pentecost sequence (Veni, Sancte Spiritus) calls upon the Holy Spirit, though, admittedly, as the “Lord” and giver of life. Aquinas directs his words (Lauda Sion) toward the city of Jerusalem, inviting it to praise God. Jacopone addresses the Blessed Mother Mary in the final stanzas of his sequence for Our Lady of Sorrows (Stabat Mater). And Wipo summons Christians to praise the paschal victim (Victimae paschali laudes).

These are not typical hymns. Yet they have remained in the treasury of the Church’s poetry and continue to inspire the faithful today.

Practical Concerns

Singing a sequence means Mass will go longer. In American culture, longer means more boring — at least at church. In sports, extra innings in a baseball game ratchet up intensity. In social gatherings, longer means successful interaction — a desire that the event will never end. Salespeople strive to lengthen conversations with clients. Goodness, even if you get an extra hour of sleep some night, that is priceless. However, at church, we are programmed to think that extra minutes mean extra grumpiness. It doesn’t have to be that way.

Good liturgy unfolds at its own pace. Instead of rushing to complete the necessary components for a celebration, it treats the parts with respect. It takes the time anyone would take with something important. The liturgy of the Catholic Church presumes that you like to pray. On solemnities and feasts, the office of readings in the Liturgy of the Hours presumes you may like to extend the celebration with vigils. It offers you extra canticles, antiphons and a Gospel passage, just in case. If that weren’t enough, it even allows a homily in communal celebration. Contrary to American culture, the liturgy presumes that longer is better. Liturgical length means your time here is so special that you don’t want it to end. A sequence extends your experience because it presumes that you, like a child at bedtime on a birthday, want more time to celebrate.

Obligatory or Optional?

There used to be many more sequences in the Catholic liturgy. We have records of dozens of them. They probably fulfilled a need similar to the one we feel whenever we sing a hymn. The words of a hymn are usually not Scripture, though they may be based on a passage from the Bible. A hymn’s words have a meter, and they usually rhyme. That creates art, which in turn reminds us that we need something outside ourselves to express eternal beliefs.

Nonetheless, recognizing the other duties that may keep the faithful from praying as often and as long as they otherwise may desire, the missal has reduced the number of sequences to four. It further reduces those to two that are obligatory and two that are optional.

The two obligatory sequences apply only to the day, not to the vigil (cf. General Instruction of the Roman Missal, No. 64). The complicated liturgy of the Easter Vigil, which seems to have everything except the proverbial kitchen sink, does not include the sequence. Wipo’s hymn announces the Resurrection, so its omission at the vigil keeps it from usurping the big news to be revealed in the proclamation of the Gospel. By Easter Sunday morning, the word is out that Christ is risen, so the sequence is faithfully sung before the Gospel.

The Pentecost sequence similarly associates with the readings of the day of Pentecost, rather than those of the vigil. The vigil readings (especially the Gospel) presume that the observance of the coming of the Holy Spirit will occur the next day. The ordo published by Vatican City for use in the Diocese of Rome gives permission — for pastoral reasons — to use the readings of Pentecost Day on Saturday evening. The same permission appears in ordos in the United States. In that case, the sequence is sung during a Saturday Mass that anticipates Pentecost by using the readings of Sunday. Technically, changing the Pentecost Saturday evening readings to those of Pentecost Sunday makes it an anticipated Mass, rather than a vigil Mass. Many people use those terms interchangeably, but there are only a few true vigil Masses in the calendar, with their own readings and presidential prayers.

The other two sequences are not required. Lauda Sion is a theologically and spiritually rich poem for the celebration of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ. The Lectionary offers an abbreviated, more pastorally acceptable version, but many parishes simply omit this sequence because of its length. In parts of the world where this solemnity remains on its traditional Thursday as a holy day of obligation, its inclusion may be more welcome. People have set aside time for this Mass and may more peacefully enjoy the beauty of its sequence.

Stabat Mater, on the other hand, accompanies the liturgy for Our Lady of Sorrows, which is typically observed on a weekday. This sequence may be recited or sung, but often it is set aside, again, because of its length. Many people who make time for weekday Mass plan for it to go no longer than expected.

When to Sing

The sequence is to be sung before the alleluia (cf. GIRM, No 64). This changes the former practice, where it followed the alleluia and immediately preceded the Gospel. When the post-conciliar rules for the liturgy first came out, the Ordo Cantus Missae repeated the former instructions: alleluia first, sequence next. The GIRM originally gave no instructions on when to sing the sequence, but the third edition of the Roman Missal clearly notes that the sequence has changed position. The result is that the alleluia remains in every way the Gospel acclamation.

The GIRM is less clear about posture. Do the people stand or sit? It directs that they sit during the readings before the Gospel and during the psalm, and that they stand for the alleluia and the Gospel (cf. No. 43). So, for the sequence, do the people remain seated because the sequence no longer immediately precedes the Gospel? Or do they stand because the readings are over? Most likely, they are expected to remain seated in anticipation of the Gospel acclamation, but the GIRM does not explicitly say.

Some parishes schedule a musical setting of the sequence that all may sing together. Others ask people to alternate the verses from one side of the church to the other. Some parishes invite everyone to recite all the words. Still others have the reader or cantor sing or recite the entire sequence.

At Easter, the sequence is optional throughout the octave, which includes the following Sunday. Parishes wanting to help people learn a musical setting of Victimae paschali laudes could schedule it again after the second reading on Divine Mercy Sunday. Similarly, it may be recited or sung on all the weekdays of the octave.

Dies Irae

Perhaps the most renown of all the traditional sequences is the one written for funerals: Dies Irae. Its authorship is typically attributed to another writer of the thirteenth century, the Franciscan Thomas of Celano (d. 1255/60). Formerly part of every Catholic funeral, it was removed from that liturgy after the Second Vatican Council but given a place in the Liturgy of the Hours. During the final week of the Church year, the complete text, broken into thirds, may be sung to start the office of readings, morning prayer and evening prayer. In the United States, people may use it for those same offices on All Souls’ Day.

Do we need a sequence? Well, consider it this way: We need art. We need poetry. We need music. We need prayer. We need tradition. We need a way of expressing the gift of our faith. Why not adorn the liturgy with a sequence?

FATHER PAUL TURNER is pastor of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in Kansas City, Missouri, and director of the Office of Divine Worship for the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph.