Conclave

Going inside and exploring the history of a papal election

D.D. Emmons Comments Off on Conclave

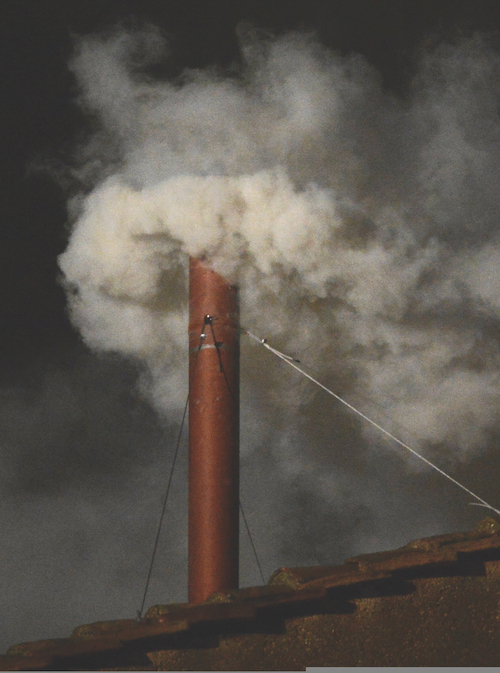

Few events on the world stage create more attention than a papal election. People everywhere, Catholic and non-Catholic, are riveted by the news as they watch the Church transition from one Vicar of Christ to another. Everyone waits anxiously for the white smoke from the Sistine Chapel that indicates a new pope has been chosen and it is proclaimed,“Habemus papum” (“We have a pope”).

Papal history is filled with interesting times and situations — for example, many of the first popes were martyred; there have been assassination attempts; one pope was kidnapped; five popes considered themselves prisoners in the Vatican; there was a time when there were three popes; for 70 years the address of the bishop of Rome was Avignon, France. These events were unique, but perhaps the most unique, the most remarkable, was in the 13th century when there was a nearly three-year period when no pope was elected; for more than 1,000 days, the chair of Peter was empty. The chaos associated with this dilemma led to the development of the way we elect popes today — that is, the process known as the conclave.

The first popes, the bishops of Rome, were elected by the clergy and acclaimed by the people. This was the same process that was used in the election of all bishops; the clergy acted as electors, other local bishops were the overseers of the election and the laity acknowledged the one elected with their approval or disapproval.

By the fourth century, as the Church grew, this simple process became more difficult. Most aggravating was the lack of an organized election procedure. Also, beginning in this era, the emperors and the aristocracy of Rome were inserting themselves into the papal election, often favoring one candidate over another and, at times, even appointing the pope. Later, in the sixth century, the emperor insisted on confirming each person elected as the pope.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Papal Election Facts

— “Extra omnes — Everybody out.” Words of the master of papal liturgical celebrations at the end of the cardinal oath-taking in the Sistine Chapel as the conclave begins. The intent is that everyone, except the cardinal electors and those specifically assigned at that time to preach to the cardinals on their important responsibility, are to leave the presence of the electors.

— 120 cardinals. The number of cardinals who participate (vote) during the papal election. No cardinal who has reached the age of 80 (at the time the Holy See becomes vacant) may participate in the vote.

— The pope appoints every cardinal, who as a group makes up the College of Cardinals. This college is not a divine institution, such as the College of Bishops, yet under the guidance of the Holy Spirit they are called to elect the Vicar of Christ — the pope.

— The last non-cardinal elected as pope was Urban VI in 1378.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Almost every head of state wanted to have control of the papacy because all their subjects looked to the Church as the center of their life. If indeed a monarch was instrumental in getting his choice for pope elected, that king or queen would have tremendous influence over the populace, as well as over the affairs of the Church.

The papacy was rich in material goods and possessed enormous amounts of land, both of which were in demand by the monarchy. In the 11th century, Pope Nicholas II (r. 1059-61) issued instructions in a papal bull, In Nomine Domini, that ended interference by an emperor or the aristocracy in a papal election. Nicholas gave the role of electing the pope to the cardinals. The cardinals were responsible for electing the pope and then the clergy and laity would approve the selection. So, the extensive role of the cardinals in today’s papal elections and in the Church can be traced to the 11th century and Pope Nicholas II. The Second Lateran Council in 1139 eliminated the requirement for all the clergy and the laity to approve the election.

Three Years Without

When Pope Clement IV (r. 1265-68) died in the city of Viterbo, north of Rome, on Nov. 29, 1268, the cardinals were summoned to elect a successor. It took the cardinals until Sept. 1, 1271, to choose a new pope. The situation that confronted and divided the cardinals was the role of France in the affairs of Italy, in the affairs of the Holy See. The electors were not necessarily unreasonable or stiff-necked people. Four of the electors would go on to become popes.

These cardinals knew well the importance of what they were tasked to do in the life of the Church but would not compromise on the issue of France having increasing influence in papal and Italian policies. Out of the 20 electors, there were seven French cardinals supporting such influence and seven non-French cardinals who strongly opposed it. They were at a stalemate almost from the beginning. The slowness of the process had an impact on the entire Church and especially on the citizens of Viterbo.

In late 1269, after months of no progress and to force a decision, the frustrated locals locked the cardinals in a palace, took the roof off the building and stationed soldiers outside. This was the beginning of what would become the conclave process for electing a pope. The Latin word conclavis means “locked with a key.” At Viterbo, the citizens also withdrew food from the cardinals except for bread and water. At length, the electors selected three cardinals from each side to form an election committee, and that committee chose Tedaldo Visconti, who took the name Pope Gregory X. Visconti was not a priest, certainly not a cardinal, and at the time of his election was in Palestine as part of the ninth crusade led by King Louis IX of France. On March 19, 1272, Visconti was ordained a priest, then consecrated a bishop and crowned as pope on March 27 of that same year.

The election of Gregory X (r. 1271-76) was a victory of sorts for the French cardinals because the new pope had previously served the Church in France and, when elected pope, was assisting Louis IX. Less than a month into his papacy and aware of the need for certain papal reforms, Gregory called for an ecumenical church council to be held in Lyon in 1274. This council would become known as the Second Council of Lyons.

High on Pope Gregory’s list of issues was the establishment of procedures for conducting a papal election. Accordingly, with the support of the Church Fathers, he issued a document titled Ubi Periculum. Some of the key features of this constitution to be used after the death of a pope included: the election of a new pope would begin within 10 days in the city where the pontiff died; the cardinals would gather in the palace of the pope, be housed in one common room with no partitions, locked in so there were no communications between the cardinals and the outside world; if there was not an election within three days, the cardinals would receive only one dish for each of their meals and after five days receive only bread and water.

While Ubi Periculum set the foundation for future conclaves, the procedures were not always used when electing a pope. The ruling pontiff could simply rescind or suspend the decree and go in a different direction. Pope John XXI (r. 1276-77) rescinded the decree, and the upshot was that when Pope Nicholas IV died in 1292, it was two years before a new pope was elected, partly because there was no clear-cut election process.

There is a story that, during that election, Charles II of Anjou, king of Sicily and Naples, attempted to persuade the cardinals to move on with the election. Charles’ efforts failed, and as he was returning home, he asked a monk he knew, Pietro del Morrone, to write a letter to the cardinals telling them that God would chastise them for their lack of action. Upon receiving the letter, the cardinals unanimously elected Morrone as pope. He took the name Celestine V, reigning from July 1294 to December 1294. This story may not be completely true, but Morrone was a monk and was elected as the pope. Also, as Pope Celestine, he reinstated Ubi periculum in 1294.

Role of the Cardinals

Initially, the cardinals were simply advisers to the pope, but over the centuries they have become heads of the different Vatican Curia departments and many hold the position of archbishop in dioceses around the world. Of course, in the present day, a primary responsibility of the cardinals is to elect the pope.

“The right to elect the Roman pontiff belongs exclusively to the cardinals of Holy Roman Church, with the exception of those who have reached their eightieth birthday before the day of the Roman pontiff’s death or the day the Apostolic See becomes vacant. The maximum number of cardinal electors must not exceed one hundred and twenty” (Pope St. John Paul II, Universi Dominici Gregis, No. 33). This right of the cardinals to elect a new pope is also specified in the Code of Canon Law, No. 349.

When a pope dies, or the chair of Peter is vacant, such as the result of resignation, “fifteen full days must elapse before the conclave begins, in order to await those [cardinals] who are absent; nevertheless, the College of Cardinals is granted the faculty to move forward the start of the conclave if it is clear that all the cardinal electors are present; they can also defer, for serious reasons, the beginning of the election for a few days more. But when a maximum of twenty days have elapsed from the beginning of the vacancy of the see, all the cardinal electors present are obligated to proceed to the election” (motu proprio Normas Nonnullas). This action of Pope Benedict XVI (r. 2005-13) amends previous instructions provided by Pope St. John Paul II, who did not offer the latitude of moving the conclave start date forward.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Conclave Miscellany

— In the past 100 years, from 1924 to 2024, there have been seven papal elections.

— Traditionally, there were three ways to elect a pope: Scrutiny — that is, by vote. Compromise, through a committee selected by the cardinals. Acclamation, in which everyone agrees on a new pope without a vote. In 1996, Pope St. John Paul II eliminated election by compromise and acclamation.

— Beginning in the 17th century, the monarchs in Christian countries were given veto power over one candidate being considered for the papacy. This power was exercised through the cardinal representative of that country. The veto power was used occasionally until 1903, when it was rescinded.

— When a pope is elected, and while still in conclave, the cardinal dean asks the electee, “Do you accept your canonical election as the Supreme Pontiff?” The electee is also asked by what name he will be known. From this point, the chair of Peter is no longer vacant.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Immediately upon the death of a pope, or his resignation, the officials holding key Vatican or Curia positions, with only two exceptions, are obliged to resign. This is done because these individuals have been carrying out the duties as directed by the pope, but since that individual is no longer in office, they can no longer act on his behalf. The new pope will decide on leaders of the key Vatican offices. Routine matters regarding the running of the Church will be left to the College of Cardinals. Critical issues and decisions will be delayed until a new pope is in office.

Among the important Vatican positions, still little known to most Catholics, is the cardinal known as the “camerlengo,” or chamberlain, of the Church. The camerlengo is among the two Vatican officials who are not obligated to vacate their office when a pope dies or resigns (the other is the major penitentiary).

One of the camerlengo’s primary duties is to officially verify, in the presence of others, that the pope is dead. At one time, he carried out this verification by tapping the deceased pope’s forehead with a small mallet and calling out the pope’s baptismal name. Today the act of determining that the pope is dead is done by a medical person and the camerlengo advises the cardinal vicar of Rome, who in turn notifies the people of Rome. The camerlengo breaks the fisherman’s ring of the deceased pope, which is an indication of the end of papal authority and ensures that the seal of the ring is not somehow used for fraudulent activities.

At some point, the camerlengo seals up and secures the papal apartments and the papal palaces in Rome: the Apostolic Vatican Palace and the palaces of the Lateran and Castel Gandolfo. A key responsibility of the camerlengo is to work with the College of Cardinals in organizing the papal funeral and assisting in the preparation for and management of the papal election; he is also charged with “safeguarding and administering the goods and temporal rights of the Holy See” (Universi Dominici Gregis, No.17).

The College of Cardinals, headed by the dean, meets daily before the election to discuss a variety of subjects and issues regarding the Church. These meetings are known as either a general congregation or a particular congregation and are held during a vacancy of the Holy See. A general congregation consists of all the cardinals who deal with significant issues of the Church. During the first general congregation, the cardinals “swear an oath to observe the prescriptions contained herein and to maintain secrecy” (No. 12). The particular congregation is made up of the camerlengo and three cardinal assistants. These assistants change every three days. The particular congregation focuses on routine matters regarding the running of the Vatican and routine universal Church issues.

While no campaigning is to be done in these congregations, that is not to say that in private meetings the cardinals do not discuss the election. All cardinals attend the daily meetings, but only those who have not reached the age of 80 at the time of the pope’s death can vote in the papal election. The congregations may be the first time that some cardinals have met one another. In August 2022 German Cardinal Walter Brandmuller suggested that cardinal electors be limited to those living in Rome because cardinals in distant countries have little or no experience with the operation of the Roman Curia or dealing with the problems of the universal Church. The Vatican response to this idea has not been made public.

The Conclave Begins

The conclave begins with the cardinals attending the Mass For the Election of the Roman Pontiff. At some point following Mass, the cardinals process as a group to the Sistine Chapel singing the Veni Sancte Spiritus. Here, where the election will take place, the cardinals take an oath to keep secret everything that takes place in the conclave.

They say, in part: “In a particular way, we promise and swear to observe with the greatest fidelity and with all persons, clerical or lay, secrecy regarding everything that in any way relates to the election of the Roman pontiff and regarding what occurs in the place of the election, directly or indirectly related to the results of the voting; we promise and swear not to break this secret in any way, either during or after the election of the new pontiff, unless explicit authorization is granted by the same pontiff; and never to lend support or favor to any interference, opposition or any other form of intervention, whereby secular authorities of whatever order and degree or any group of people or individuals might wish to intervene in the election of the Roman pontiff” (No. 53). They then say, “I do so promise, pledge and swear.” Each cardinal places his hand on the Gospels, and says, “So help me God and these holy Gospels which I touch with my hand.”

Once the conclave begins, the cardinals are not allowed to leave except for illness or other grave reasons.

The cardinal electors will have no communication with the outside world during the conclave: no radio, television, newspapers, computers or cell phones. The facilities used by the cardinals will be swept for listening devices and electronic jammers to deny any communications from being broadcast to or from the places the cardinals occupy. The objective is to ensure the electors are protected from any outside influence. The people who will support the cardinals in the conclave — cooks, domestics, confessor priests, two doctors, anyone — also take an oath of secrecy. This group includes “the Secretary of the College of Cardinals … the Master of Papal Liturgical Celebrations with two Masters of Ceremonies and two Religious attached to the Papal Sacristy; and an ecclesiastic chosen by the Cardinal Dean” (No. 46). The secrecy of the voting process in the Sistine Chapel is the camerlengo’s responsibility.

The time of sequestering the cardinals in one room with no privacy is a thing of the past. Today, the cardinals live in a modern lodging facility with comfortable rooms. There is no discomfort in the same sense as that of conclaves of the past such as, when everyone was in one room with, at best, a curtain dividing participants. Now they lodge in a Vatican residence, Domus Sanctae Marthae, which was built in 1996 to provide accommodations during the conclave and to house visitors to the Holy See. Each room or suite has been described as simply furnished with a bed, desk and chair. Distancing the cardinals from any outside influence during their daily journey from their place of lodging to the Sistine Chapel where they vote is carefully observed.

The Vote

The rules for the conclave, including procedures for voting, are prescribed in Pope St. John Paul II’s 1996 apostolic constitution, Universi Dominici Gregis, which we’ve already referenced several times. Voting is by ballot, called scrutiny, and a two-thirds majority is required for an election. “Should it be impossible to divide the number of cardinals present into three equal parts, for validity of the election of the Supreme Pontiff, then one additional vote is required” (No. 62).

Voting takes place twice in the morning and twice in the afternoon. The size and form of the ballot used is carefully defined, as well as how the ballot will be filled out. Each cardinal elector secretly writes the name of the person he chooses on the ballot. When voting takes place, no one else is in the room except the cardinals.

The ballots cast are gathered, counted and verified in a very prescribed manner. Each day, during the two votes in the morning and afternoon, nine cardinals are selected to count and verify the vote. The ballots are counted after each vote — if no one receives a two-thirds majority, there is no new pope. Conversely, if anyone gets a two-thirds majority, then a pope has been elected.

The voting results are documented by the cardinal camerlengo or his assistants. Immediately after one vote is cast, and if there is no pope elected, then another vote is taken and counted. After each of the two votes in the morning and afternoon, the ballots are burned in a stove installed in the Sistine Chapel. The black or white smoke, indicating whether or not a new pope has been elected, is caused by chemicals added to the fire.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Pope Francis’ 11th Anniversary

March 13, 2024, marked the 11th anniversary of Pope Francis’ election by the papal conclave. The anniversary date is a national holiday in Vatican City.

Pope Benedict XVI resigned on Feb. 28, 2013, and the papal conclave, which began March 12, 2013, elected Jorge Mario Bergoglio, archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, as the 266th pope on the fifth ballot on March 13, 2013. He chose the name Francis in honor of St. Francis of Assisi.

Pope Francis is the first Jesuit pope. He is also the first pope from the Americas and the Southern Hemisphere.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

If three days of voting pass without a new pope being selected, voting is suspended for one day. The vote is then resumed as before with no more than seven ballots cast. If there is still no election, there is another pause followed by seven more ballots. Again, if there is no one elected, another pause is taken and then seven more ballots. Each pause includes prayer and discussions.

Should, after all this voting, a new pope is still not elected, the cardinals will discuss how to proceed so that they can accomplish their task. The guidance in Universi Dominici Gregis reads, “Nevertheless, there can be no waiving of the requirement that a valid election takes place only by an absolute majority of the votes or else by voting on the two names which in the ballot immediately preceding have received the greatest number of votes, also in this second case only an absolute majority is required” (No. 75). Since the beginning of the 20th century, no conclave has lasted more than four days.

D.D. EMMONS writes from Pennsylvania.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Timeline of the 2013 Conclave

On Feb. 11, 2013, World Day of the Sick, Pope Benedict XVI announced he would resign: “After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry. … With full freedom I declare that I renounce the ministry of Bishop of Rome, successor of St. Peter, entrusted to me by the cardinals on 19, April, 2005, in such a way, that as from 28 February, 2013, at 20:00 hours, the See of Rome, the See of St. Peter, will be vacant and a conclave to elect the new Supreme Pontiff will have to be convoked by those whose competence it is.”

On Feb. 13, 2013, at a final public Mass on Ash Wednesday, Pope Benedict XVI said, “Tonight there are many of us gathered around the tomb of the Apostle Peter, to also ask him to pray for the path of the Church going forward at this particular moment in time, to renew our faith in the Supreme Pastor, Christ the Lord.”

On Feb. 14, 2013, Meeting with Parish Priests and The Clergy of Rome, Pope Benedict XVI said, “It is our task, especially in this Year of Faith, on the basis of this Year of Faith, to work so that the true council, with its power of the Holy Spirit, be accomplished and the Church be truly renewed.”

On Feb. 28, 2013, greeting the faithful of the Diocese of Albano, Pope Benedict XVI said, “I am simply a pilgrim beginning the last leg of his pilgrimage on this earth. But I would still, thank you, I would still — with my heart, with my love, with my prayers, with my reflection, and with all my inner strength — like to work for the common good and the good of the Church and of humanity.”

Feb. 28, 2013: farewell address to eminent cardinals. Quoting theologian Romano Guardini, Pope Benedict XVI said, “’The Church is reawakened in souls.’ The Church is alive, she grows and is reawakened in souls who — like the Virgin Mary — welcome the Word of God and conceive it through the action of the Holy Spirit; they offer to God their own flesh.”

March 1: Formal invitation to the conclave is issued.

March 4-11: General congregations to pray and assess the Church needs.

March 12-13: Election.

On March 13, the cardinals voted overwhelmingly for Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio on the fifth ballot. When Cardinal Bergoglio was asked if he would accept his election, according to Cardinal Wilfrid Napier, OFM, he said, “Although I am a sinner, I accept.” He took the name Francis, in honor of St. Francis of Assisi.

March 13: At 7:06 p.m. local time, white smoke and the sounding of the bells of St. Peter’s Basilica announced that a pope had been chosen. Cardinal Protodeacon Jean-Louis Tauran announced the election of the new pope, including his name, and Pope Francis appeared and asked the world to pray for him.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..